What the pro-life movement could have learned from the temperance movement

Lessons from America's largest, longest reform movement

At the time of the American Revolution, it was perfectly acceptable to drink alcohol, even heavily.

But by the time of the Civil War, if you were a respectable, upwardly-mobile American, you were almost certainly a teetotaler. Well, at least in public.

Sixty years after that, anti-alcohol forces achieved legislative nirvana—an unfathomable triumph in today’s political paralyzed context—a constitutional amendment1 banning the manufacture, transport, and sale of alcohol.

But just 14 years after that astounding success, everything the movement had pursued and won came crashing down, legislatively and culturally, with the repeal of Prohibition by another constitutional amendment. Outside of some pockets of evangelicalism (and even those have rapidly eroded), the temperance movement—arguably the largest, longest-lasting, most successful reform movements in American history—is no more.

Hell, I started drinking while writing my dissertation on the 19th century portion of it. Somehow reading melodramatic stories like “Ten Nights in a Bar Room” wasn’t convincing (temperance stories are literally the same story, by the way, like the 19th century version of the Jurassic Park movies). And if you lose the weird evangelical missionary kid, whose childhood was a hermetically sealed religious time capsule, you are indeed not doing great.

Most Americans have probably never heard of the temperance movement, or at least they conflate it with the push for legislative Prohibition. But that’s not how things started.

And the pro-life descendants of temperance reformers—and American evangelicals more generally, as they have dominated both movements—would do well to consider both the rise and the fall of the temperance movement if they want any long term influence in American culture. 2

First, a very brief history of temperance and Prohibition. Yes, I will make it interesting with gifs and memes.

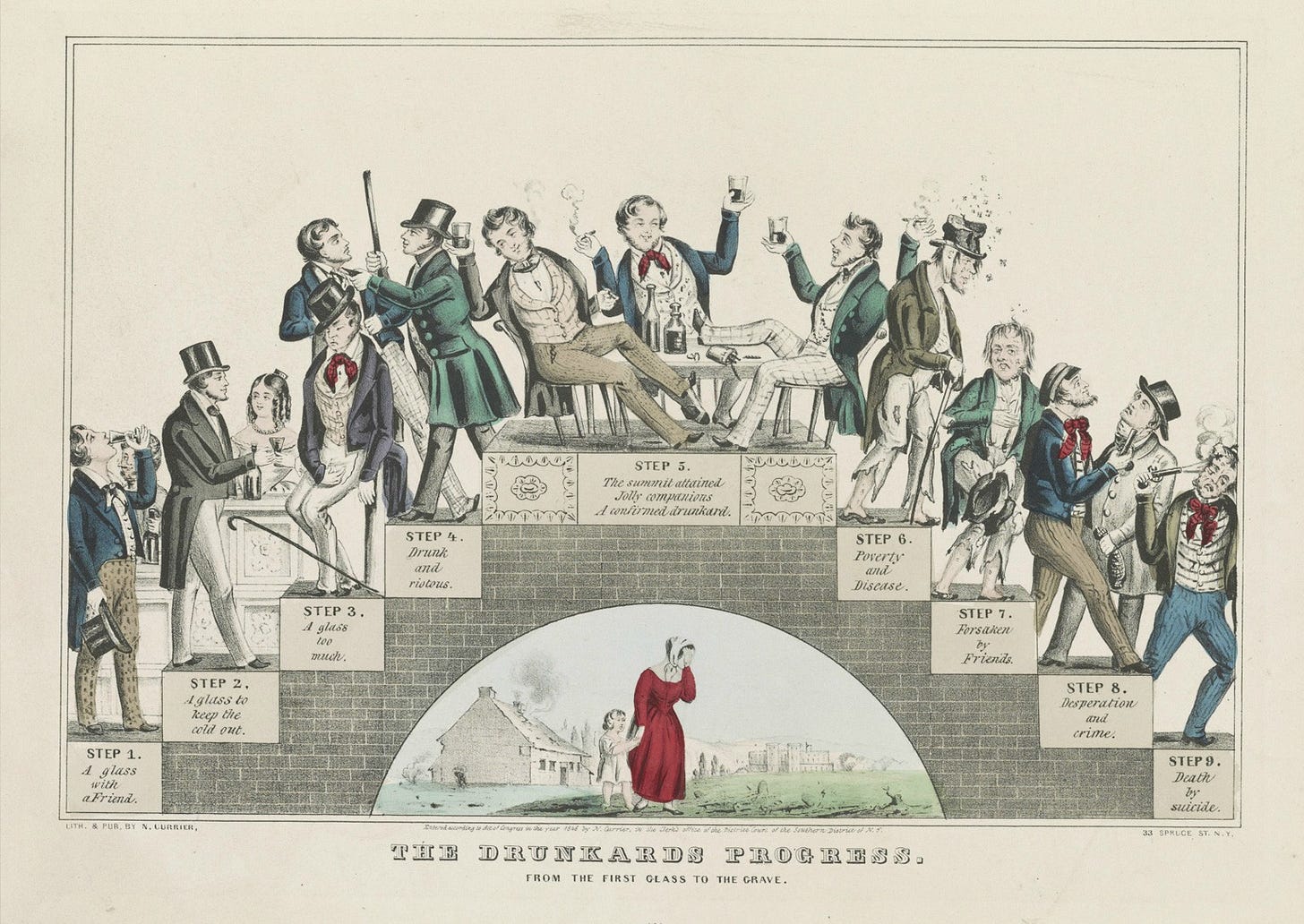

Long before the era of rum-runners, speakeasies, and moonshiners, the temperance movement convinced millions of Americans to voluntarily quit drinking. Temperance began in pursuit of a larger utopian vision for society in wake of the massive political, economic, and social changes—at once exhilarating and terrifying— unleashed by the the American Revolution and the advent of an industrializing, market-based economy.

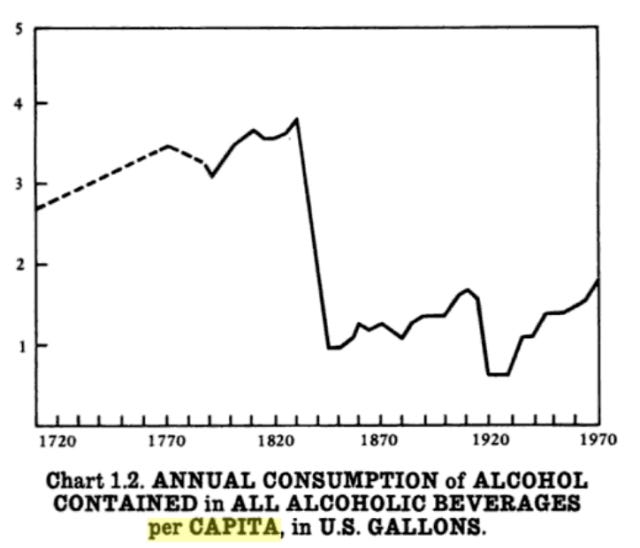

And, quite frankly, Americans had a pretty serious drinking problem when all this got started. Alcohol consumption was triple the amount per capita compared to today. I mean, 18th century babies drank.

Temperance was just one of a pantheon of antebellum reform and voluntary movements that sought to mitigate the potential downsides of these changes and harness them for good. Antebellum reform paired well with an optimistic, post-millennial form Christianity emanating from the Great Awakenings that argued human beings could actually perfect society and thus usher in Christ’s return. It seemed to many antebellum Americans that the United States might just be the vehicle for human perfection.

In the antebellum temperance mind, societal perfection began with self-improvement and self-mastery. Refraining from drink was an easy way for an ambitious man3 in a nation-on-the-rise to be a more good-hearted father in the sentimentalized family, a more clear-headed worker in the industrializing work place, a more successful and productive citizen all around. At scale, this individual betterment, reformers hoped, would create more stable homes in which to protect and provide for women and children, more reliable and diligent workers in the new market economy, and the virtuous citizenry the Founding Fathers had identified as essential to America’s representative government.

For temperance reformers in the movement’s heyday, “moral suasion,” not force of law, was the preferred vehicle. But even before the Civil War, the idea that government might eradicate the great social evil of alcohol much more efficiently began to have some appeal.

Antebellum temperance reformers had spectacular success. By the Civil War, half of all Americans had quit drinking.

Of course, as with almost everything in American life, antebellum reform ran into the brick wall of slavery. How far the utopian push for a perfected society needed to go and how much human equality should be involved was a matter of dispute and eventual civil war. You can clearly see the tension in both 19th century reform and 19th century Protestantism between societal liberation and societal control. That tension was nowhere more more satisfactorily resolved than in the temperance movement. Whether the ultimate goal was social order or social progress, a broad consensus of Americans agreed that temperance was essential.

On the one hand, more radical reformers placed temperance within a broad ideology of promoting human dignity and equality that demanded the abolition of slavery and women’s rights. Alcohol, with slavery and sexism—some reformers added class-based oppression—was part of an unholy trinity of social ills that prevented the young nation from achieving its potential (and of course, bringing Jesus back).

On the more conservative side of the equation, temperance was key to maintaining social order in the midst of the era’s swirling change. Temperance was never as popular in the South, with its more “traditional” ways (i.e. sitting around drinking hooch in a field), but even so, many slaveholders saw abstinence as a bulwark for their authority and ability to maintain a racial and gendered order. More conservative northern reformers likewise argued that sober husbands and fathers undercut a key feminist argument, that women needed more equality because drunken, abusive men weren’t keeping their end of the patriarchal bargain.

The Civil War tamped down Americans’ optimistic streak and resolved, in their minds at least, the issues of slavery and race. Reuniting the country and reestablishing order—especially racial order, in the wake of slavery’s end, new civil rights for Blacks everywhere, and an increase in non-white and/or non-Protestant immigration—became more important than the pursuit of societal perfection. Americans, North and South, were eager to paper over their differences and raise a glass of water together.

The war also redefined the role of government, particularly the federal government, by forcefully quashing the claim that states could secede and by legally overruling their authority over individual civil rights (sort of, in theory, we’ll get back to you in about a century). A major antebellum reform movement, abolition, had achieved its goal through government power, and radical reformers after the war saw, correctly, that continued government activism would be needed far into the future to make sure slavery didn’t return under some other guise.

Although the war dealt a blow to the temperance lifestyle, particularly its connection to successful manhood—General Grant was known as a drinker, even while he racked up battlefield success—temperance as a movement once again became a convenient, unifying way to channel perky reformist energy while shoring up social order. Nativists loved temperance as a way of differentiating WASPs from immigrants, pushing cultural assimilation, and arguing for immigration restrictions. On the other hand, the burgeoning women’s rights movement glommed onto temperance as a safer, more acceptable form of female activism. Frances Willard, the savvy leader of the popular Women’s Christian Temperance Union, glorified female victimhood while quietly advancing greater female autonomy (sometimes her own members didn’t fully catch on to her schemes).

Another development that pushed temperance towards Prohibition was a (new and improved!) split in American Protestantism between modernists and fundamentalists that centered around biblical interpretation. This was in many ways a rehashing of the antebellum Protestant split over slavery, which similarly rested on divergent biblical interpretations, with southerners adhering to a more literalist one. In the late 19th century, however, the modernists went further into biblical criticism and theological liberalism, and the fundamentalists reacted by codifying “inerrancy,” which is the centerpiece of white evangelicalism to this day.4 As the 19th century slid into the 20th, fundamentalists felt increasingly embattled in a modernizing, religiously diversifying American culture and aimed at achieving greater political power to make up the difference. Prohibition was the perfect vehicle, it seemed. 5

For all these reasons, after the Civil War and heading into the Progressive Era, temperance reformers looked more and more to the law, to controlling American habits by force rather than persuasion. The legal march started small, on the local level, with Sunday laws or other limited bans, then graduated to state legislation, before the Anti-Saloon League—the first single-issue pressure group in US political history, which pioneered legislative lobbying—set its sights on a total, constitutional ban on the production and sale of alcohol.

Like the 19th century temperance movement, Prohibition rode both a progressive reformist wave that looked to government policy as the solution to social problems and a revanchist one consumed with anxiety over social change. Anti-German sentiment (German Americans brewed much of the alcohol around here) during and after World War I greased the skids. Through this skillful, somewhat bifurcated appeal and incredibly good organization, the 18th amendment was ratified in 1919.

Prohibition was probably a massive overreach that was doomed to fail under any scenario, but the timing was particularly awful. Post-World War I, the growing numbers of urbane and urbanized Americans were in no mood for self-denial in the bubbly economic boom of the 1920s. The automobile and rising college attendance gave young people new found freedom. Women got the right to vote and demanded even more freedom,6 starting with their clothing and personal habits.

The law, which banned something that had been legal for centuries, was always going to be difficult to enforce, and the amendment’s failure to establish clear lines between federal and state authority didn’t help. Organized crime filled the demand and expanded the assault on law and order more generally. 7

The Depression ultimately finished off Prohibition. The government needed the tax revenue, and the economy needed every boost it could get. Prohibition was repealed by the 21st amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1933.

With the Dobbs decision, another American reform movement has grasped what it believed was its Holy Grail. And like the bad Nazi guy in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, that cup is going to prove fatal, just as the 18th Amendment did for temperance.

The pro-life movement should have learned some lessons from history, but people so rarely do, at least not beyond the final exam at the end of the semester (there will also be one at the end of this article. Kidding. Maybe). Here’s a few pointers:

Persuasion is harder than law for bringing social change, but the results are usually more durable. Is it easier to make people do what you want rather than convincing them to do it on their own? Absolutely. There’s a reason dictatorship is popular. There’s a reason democracy hasn’t broken out everywhere. But no one really likes dictators, and given half a chance, they usually try to overthrow them.

Of course, you could argue that Prohibition was democratic, that people did want it, in that a constitutional amendment was ratified, no casual walk in the park. And American majorities continued to vote for dry candidates in the 1920s. But the end results demonstrate that most people wanted Prohibition mainly in the abstract. They probably supported it because a century of temperance work had led them to believe they should and/or it was associated with other cultural markers (i.e. If you were a nice white Christian, you were pro-dry).

Post-Dobbs—when voters have demonstrated their support for abortion rights even in red states like Kansas—it does appear that many pro-lifers were more comfortable with that stance in the abstract, too. Being anti-abortion has been a cultural/political/religious shibboleth that speaks to broader identities (the quickest way to not have any friends at all in an evangelical community is to declare yourself pro-choice. Or gay). But when push has come to shove, it seems folks aren’t as pro-life as they themselves thought.

In terms of results, the pro-life movement actually had spectacular success using persuasion under Roe. The number of abortions has plummeted since 1973 (it has actually begun creeping back up under Dobbs). Now, I’m not sure how much credit the movement deserves; better forms of birth control, which pro-lifers have usually opposed, probably account for most of the decline. But the discussion of abortion in moral terms combined with better ultrasound technology probably has changed some hearts and minds, too.

Most Americans have come to support abortion being “safe, legal, and rare,” with an emphasis on “rare.” The pro-life movement’s insistence on force and total victory and the bungled results of their achievement has shifted Americans’ focus to the “safe and legal” part of that equation. People who generally dislike abortion are coming to the conclusion that government can’t possibly manage the complex issues involved and are more open to getting government completely out the way.

The temperance movement also had its greatest, enduring success with persuasion. Per capital consumption dramatically plummeted from 1830-1860, and, while it’s waxed and waned somewhat since, it has never approached pre-1830 levels again. In addition, the methods and ideas behind Alcoholics Anonymous, which is widely seen as the most effective sobriety program, were honed during the antebellum temperance movement.8

Marry your cause to a positive, uplifting vision. Temperance at its height inspired people to change their behavior as part of a broader belief that that they could be better Americans and that American society could be a better place. Temperance reformers supported many other causes that demonstrated their sincerity.

By the 1920’s, Prohibition, like the pro-life movement in our own time, came to be identified with the pursuit of a narrow religious program and with helping a particular religious subculture gain political power even as their overall beliefs and practices declined in popularity. Not exactly an inspiring appeal for the average American.

The pro-life movement could have spent the last 50 years pursuing more universally appealing policies that expanded the social safety net for families with children, reduced maternal mortality and child poverty, and generally made it more possible for women to have children and to raise them in more humane conditions. In support of this, they could have built a broad-based, unifying coalition. That’s obviously the opposite of what they did.

And despite lots of promises to support women and babies post-Dobbs, they are still not doing that. It’s pretty obvious this movement was never about women and babies, or more generally about bettering society. It was about social control and winning power.

Outlawing something that has long been legal requires massive government intervention. Consider carefully whether it’s worth it. Government can’t and shouldn’t do everything, and in a democratic society, governmental power must be balanced with citizens’ freedom. As a general rule, it’s not gonna go great when government directly grabs more of that freedom. Enforcement of those laws pushes government into potentially more authoritarian practices. Non-enforcement risks undermining government’s credibility and encouraging lawlessness, as Prohibition demonstrated.

The exception is of course when some citizens are directly harming and impinging on the freedom of others. Then government MUST step in, because that is in fact the basement-level obligation of government. That is a struggle worth engaging. And so, yes, slavery, a practice that existed legally for hundreds of years and shaped and defined southern life, had to be outlawed. And that, too, was never going to be easy. Federal troops occupied the South for a decade after the Civil War, that’s how hard it was, and still the job was not even close to being done when they left in 1876. Almost immediately, Black Americans lost all but the most thin layer of their newly won freedoms via segregation, sharecropping, and terrorism. Slavery’s demise and the continued struggle against racism, demonstrate the difficulty of changing hearts and minds by force of law, even when that must be done.

As a young, evangelical pro-life supporter, I used to see a direct parallel not between the pro-life movement and Prohibition, but between it and abolition, between abortion and slavery (yes, I know, just one of 500 things I look back on with cringe). I considered the unborn as human beings who deserved the fiercest government protection. My pro-life beliefs waned significantly with age, as I confronted more of life’s complexities, but I’ve remained troubled by abortion. I’ve always had some sympathy with the cause.

Post-Dobbs, though, the movement has lost me entirely. I can clearly see the difference between an enforceable government protection of fully formed human life, as with the Civil War amendments, and what we have now, terribly conceived social policy that requires massive, increasingly authoritarian government intervention in people’s most private affairs and endangers women’s health.

And instead of ending or even significantly reducing abortions in the United States, the Dobbs regime has given us stories of women almost bleeding to death from untreated miscarriages or having their periods monitored by various authorities, and state governments pledging to block interstate travel and search through people’s mail. Meanwhile, more liberal states have in some cases expanded abortion access beyond Roe in reaction to this absurdity.

Temperance scholar though I am, I confess that I didn’t see all of this coming. I didn’t think Roe’s demise would have such a huge effect, given how little abortion access existed in the states that would subsequently ban it and given the increased prevalence of pharmaceutical abortion.

But like their anti-alcohol forbears, the anti-abortion movement’s drive for social control and group power has trumped any aim towards building the more just and loving society they claim they want.

Their greed will ultimately destroy them, you can take that to the bank. But in the meantime, it will harm American women, not to mention well functioning democratic government.

Do you realize how impossible a constitutional amendment is? There’s a reason there’s only only 27, the last one ratified in 1992 after a college student resurrected an effort that began in 1789 to prevent Congress from raising their own salaries (salary increases now go into effect for the following Congress). For those who need a refresher, You need a 2/3 vote in both chambers and ratification by 3/4 of state legislatures. Good F-ing luck.

At this point, it appears they don’t give sh*t. Insurrection it is.

Most temperance efforts were aimed at men; women were not thought to drink very much, and those that did usually had bigger moral problems. Such as being whores.

I just have to reemphasize the point that today’s white evangelicalism is a direct descendent of southern, pro-slavery Christianity.

Ironically, a literalist reading of the Bible definitely does not support Prohibition, unless you are ready to call Jesus a bootlegger.

Greedy bitches.

Some historians of the Prohibition of Prohibition dispute that it was a failure, pointing to a dramatic drop in alcohol consumption. However, that data is suspect because so much of drinking was off the books so to speak and data wasn’t formally collected.

More specifically, the Washingtonian movement, a program of mutual support for alcoholics and their families. The Washingtonians gathered together socially, helped each other with food and other aid, told their stories to each other (often through tears), and empathetically encouraged each other’s sobriety. And it worked.

M.A.D.D. was a situational temperance movement. It’s was an alliance of “concerned mothers” and emergency room doctors and the police against one aspect of alcohol abuse in the public eye. Anyway I think it’s a great recent example of persuasion that bubbled up from the ground up. It took a long time, too.

And, it’s a pro-life victory.

People love whining about the “nanny state,” but hey, just listen to your mom for once!!

I learned so much from this about the temperance movement.

Meanwhile, your paragraph about what the pro-life movement could have focused on brought me to tears. That's a platform I would 100% support.