Russell Moore's Prophetic Journey on a Roundabout

He's not losing nearly enough of his religion. With all due respect for a man I really do admire.

I just finished Russell Moore's book, Losing Our Religion. And let me say right at the top that I am sincerely thankful for Russell Moore. I am thankful for David French, Peter Wehner, Beth Moore, David Platt, and other evangelical people of influence and integrity who have, at great personal and/or professional cost, refused to sit on the crazy train as it plunges off the cliff and have appropriately labeled the train as crazy and suspended in the air like Wile E. Coyote.

I'm thankful they are saying this, because maybe given their evangelical bonafides, a few folks might listen. And for the sake of our democracy at least in the short term, we all need someone to get through to even a few.

But the source of Moore's continued evangelical credibility is also the rub. Based on what he says in this book, it seems he (not sure about the others?) may have bailed on the current crazy train, but he has caught the very next one and is headed back around the bend. Because he continues to endorse the exact same foundational theology that has led American evangelicals to this precipice. And all the ones that came before.

I mean, Moore's (now former) denomination was literally created to defend slavery, as he readily concedes. Call me crazy, but if your church started like that, I feel like you gotta strip things down to the barest of Jesus studs and just start over, because something has gone horribly wrong. Which absolutely has not happened. Moore's version of the SBC has the same theological foundation, not to mention drywall and floorboards, as it did in 1845.

In other words, Moore rightly says the American church is very sick. But his prescription boils down to taking more of the poison it has been imbibing for the last 200 or so years. Maybe a slightly different dosage or in conjunction with some milk of magnesia to counteract it a bit better. But basically the same stuff. Of course, if he did call it poison he'd be labeled a theological liberal, like the many others who have diagnosed the problem and subsequently have been cast out as heretics. Which is exactly how the poison works to begin with. If you call it poison, you are no longer qualified to call it poison. It's a circular logic that works to preserve power and institutional culture just brilliantly.

OK. So. What is the source of the rot? What is the poison?

The answer is pretty easy.

It's the inerrancy, stupid.

Inerrancy is a .pretty modern, especially (but not exclusively) American doctrine, that solidified in the 19th and 20th centuries in response to modernist and scientific arguments that challenged traditional religious authority and the broader status quo. Darwin's theory of evolution was one powerful catalyst, as were movements for greater racial and gender equality. Inerrancy asserts that the Bible is the perfect, final authority on, well, everything, and that its interpretation should strictly adhere to the text as written without regard for the time and place in which it was written. In reality, it's impossible to interpret the Bible literally in many cases or find any answers at all to a host of moral issues in modern life. But I definitely grew up (as a Southern Baptist) with the message that all the wisdom you could ever need on any issue is in the Bible, and true Christians don't interpret the Bible, they simply read it and do what it says.

American evangelicalism of all sorts is built on an insistence of inerrancy and the elevation of the Bible as THE authority. Science, experience, history, scholarship--none of that matters. It's the Bible, and that's it, and it's a very narrow, stringent interpretation of the Bible--which has been defined and owned by white American men--and that's it. And this is what Russell Moore is straining so very hard to hold on to even as he grapples with and truly grieves over what it has wrought. But if we go through Moore's identification of the symptoms of the evangelical church's illness, we'll see that inerrancy is the disease in every case.

A loss of credibility. Moore believes many particularly young evangelicals are walking away from the church not because they don't believe in its teachings but because "they believe the church itself does not believe what the church teaches." He points to, among other things, the abuse scandals in various Christian institutions. While the evangelical church is plenty hypocritical, I think this is a rather myopic, convenient diagnosis, akin to Moore (in a different context) and others claiming that apparent overwhelming evangelical support for Trump is at least partly due to so many people calling themselves evangelical who actually aren’t.

I hate to tell you, Dr. Moore, but many people (like me) are leaving the evangelical church because its biblical interpretation, inerrancy, not only does not hold up intellectually but because it has directly contributed to the abuse and hypocrisy you discuss (Also, as Moore himself details in multiple anecdotes, there are plenty of really, truly devout and committed evangelicals who support Donald Trump. I know many, many former and current missionaries--the types of folks he regularly lauds in his writings--who are Trumpers. That's right, people who served decades in Africa and Asia. Are. Trumpers. Some of them enthusiastic ones).

Well before Trump, inerrancy eroded evangelical credibility, even as evangelicals invented it to do just the opposite. As I've said before, inerrancy oversimplifies complex problems, shuts down critical thinking, and makes no allowance for human progress, experience, scientific discovery, or change over time. It's inherently revanchist, anti-intellectual, and preserving of established power. That's why inerrantists have generally been on the wrong side of major reform movements for human rights and gender and racial equality. That's why patriarchy is still staunchly in place in evangelical institutions and why abuse is allowed to fester.

While there are of course believers in inerrancy who are also critical thinkers (Moore being one, to his credit), the culture of inerrancy greatly discourages critical thought. In fact, the great appeal of inerrancy is not having to think. You can just swallow a sure-fire, can't-miss pill whole and be forever cured and right. Not only is that mindset not credible to those of us to like to think, it is very dangerous indeed for human society. Evangelicals, by putting a premium on certainty and believing so whole-heartedly in their own rightness, are highly likely to put their cause above all else, to believe the ends justify the means. History is littered with atrocities committed by religious zealots convinced of their own righteousness.

But also--for those who can't swallow the pill, evangelical theology has no credibility not because evangelicals don't believe it enough or don’t live it out, but because it is frankly unbelievable. The idea that an ancient library of books written by different authors, many of them not clearly identifiable, in a time before any concept of human rights or democracy or nation-states or basic scientific discovery or gender equality, a time of entrenched patriarchy and tribalism and violence, is the final, clear, perfect, and unquestioned authority on all questions of human morality, belief, and existence for all people for all times--I mean, come ON. How small is your God and what has he been doing for the last 2,000 years?

A loss of authority. Moore is rightly outraged that American evangelicals have seemingly abandoned all respect for authority and truth. He's just *shocked* that the people who have argued for decades now with liberals over the existence of objective truth are the victims and purveyors of demonstrable lies.

To which I must gently say--Friend, are you really surprised that the same people who, contrary to all scientific evidence, have been taught to believe in a 6-day creation story, a 10,000 year-old planet, and a historical Adam and Eve are succumbing to conspiracy theories and snake-oil salesmen? An inerrantist view of scripture demands people refrain from believing their own eyes or their own experience in many cases, whether it be millions-years-old dinosaur bones or the improved health and well-being and loving relationships of LGBTQ people when they are allowed to accept themselves and are no longer the objects of scorn and shame. I certainly grew up believing that my feelings and even trauma were of no consequence when compared to the truth of the Bible, with which I was browbeaten when my experience didn't fit the narrative upon which the institution relied.

And we wonder why there is an abuse crisis. Evangelical abuse victims are literally conditioned to reject the leadings of their own hearts and to distrust their own instincts. There is only the Bible. And guess what, abusers can quote it chapter and verse.

Moore of course calls out those abusive, demagogic leaders who wield the Bible as a weapon. But a culture of inerrancy makes that so much easier to do, and they will continue to get away with it. Inerrancy promotes the idea that certainty about everything is not only possible, it is mandatory, that all questions--even the most unanswerable ones--especially those--have easily identifiable answers.

As political scientist Brian Klaas has demonstrated, the peddling of certainty has been one of the surest paths to power throughout human history. I would argue it is why the evangelical church grew so fast for so long. When Trump said, "I alone can fix it," evangelicals were primed to believe that message, if not the messenger (eventually they believed him, too). Evangelical theology, based on an inerrantist view of scripture, promises this kind of certainty as a matter of course. In my experience, evangelicals are practically allergic to uncertainty or moral ambiguity, and they flee from it given any chance at all.

The loss of identity. Moore laments that too many evangelicals have found their identity in a secularist political tribe rather than in Christ and Christian community and therefore they have responded to the loss of power in society through culture war rather than with humility. But here again, inerrancy has tilled the ground for tribalism. Despite Moore’s claims to the contrary, inerrancy demands, along with certainty, conformity. If the Bible is the final authority and if its interpretation is clear, there's no room for dissent. How could there be? And the social humiliation Moore speaks of as a catalyst for ferocious tribal identity and warfare is especially intense among a people who have banked everything on being absolutely and completely right about everything. Being right is central to the evangelical identity because inerrancy has made that possible. Admission of wrong or changing a position is "caving to the culture" and “abandoning scripture” and simply not an option. You risk hell itself by going astray.

How evangelicals see others, even in its most loving form, is also conducive to a tribal mindset. Evangelicals--certain that they are right and that if they don't convince you of that, you will go to hell--necessarily divide the world into "us" and "them" and doggedly pursue "them" as people who are hopelessly lost, misguided, blind, and unaware. The condescension and superiority is implicit, woven into the fabric of religious exclusivity, which is a by product of inerrancy. Moore tries to smooth out the edges by urging his readers to think of their neighbor as their "mission field" instead of their enemy. But is that really any better? Is that any more humbling? How about I think of my neighbor as, well, MY NEIGHBOR, my friend, from whom I can also receive love and from whom I can also learn. As I have grown up and moved into secular spaces, I've been pleasantly surprised at the love and wisdom I've found outside the church after being told ad nauseam that non-Christians can't love and discern the way we can.

The loss of integrity. Moore mourns the sacrifice of morality and character in order to win a fight, for the supposed greater good of a cause. Too many evangelicals have arrived at a place where the ends justify almost any means. Here again, inerrancy is the culprit. Inerrancy tells the believer that right belief is the key to character, that the Bible stands above all, they just have to sign on to a belief system and they are one of the "good guys." Inerrancy erases the humbling moral struggles and debates in life. Inerrancy states that the rules are clear and above everything else.

What we should be teaching Christians is that life is often a fraught, uncertain moral path, that the Bible is not clear on many, many issues and decision points in modern life, and that we will often not know what God requires of us. We don't follow an instruction manual, we walk by faith. Humility is the rule of the road. We can always, always be wrong, but that's why God has poured out his grace. He never expected us to get it just right. What we should be most worried about is that we have failed to love. I don't see how a Christian community that emphasized this could go very wrong. But I can see a myriad of ways that a Christian community that emphasizes certainty and "clear" biblical authority already has gone grievously, horribly wrong in church history, or even in just Southern Baptist history.

The loss of stability. Here Moore gets closest to the actual root of the problem in the evangelical church and its solution. He says nostalgia or returning to some utopian past is not the way to cure the church's ills and instead, we have to have a full reckoning with the damage. "What is not repaired is repeated," he writes, and to that I say AMEN, BROTHER MOORE.

And I wanted to stand up and cheer when he tamped down hopes of "revival," which for me conjures up memories of those dreaded, highly manipulative services after which it was pretty much mandatory to walk the aisle and "recommit your life to Jesus" or be marked by suspicion. He also gets closer than I would have expected to critiquing a religious culture that is only concerned with a list of personal behaviors and pays no mind to culture and system (Robert Jones, in his book White Too Long, demonstrates how the roots of this “personal savior” theology, which persists to this day in white evangelicalism, are inextricably linked with the defense of slavery and racism). Whether trying to stir up a tent-revival-type of "experience" or returning America to a mythical "Christian" past (in which devout Americans tolerated if not participated in racial discrimination and violence), Moore says the solution is not to "get back" to something but to renew the church for the future.

And I so very much agree. But I highly, highly doubt we will get there unless we reexamine the foundational framework of evangelicalism itself, which, again, is only a couple hundred years old at best, which has been used to prop up any number of pernicious abuses of power, which is honestly an insult to the majority of critical thinking people out there, which almost by design produces a tribalistic, dogmatic, arrogant mindset, which is easily manipulated by sociopathic leaders. Maybe we need to reconsider inerrancy? Just a thought.

That brings me to my last, and overarching, critique of Moore's position. Despite all the evident failures of evangelicalism, from slavery to misogyny to sexual abuse scandals to Donald Trump to January 6, Moore still seems so certain that the future of the church is evangelical, that the key tenets of that version of Christianity can't be compromised.

And I just cannot fathom how he would come away with that idea. Look, mainline churches have their own problems, all religious traditions do, and I've been disappointed on a number of fronts since moving over to that side. But liberal Christianity is sustainable for me. I can believe in science and be a liberal Christian. I can fully use my gifts as a woman in a liberal Christian context. I can truly love my LGBTQ brothers and sisters. I can reflect on my own failings and those of broader systems and cultures. I can challenge my leaders and their interpretations of scripture. I can ask the hardest of questions without getting expelled. I can appreciate the Bible without brainwashing myself. I can be honest. I can be free from fear. I can wonder. I can doubt. I can breathe. And most importantly, I can focus on the example of Christ instead of clinging to a facade of certainty.

Why can't that be the future, Dr. Moore? Or at least a good part of it? Why must we drag the heavy baggage of inerrancy around? I realize it’s too much to hope or ask for someone like Russell Moore to abandon a major part of his entire belief system. But perhaps he could at least concede that other kinds of Christians might have something to offer? Or even just might be Christians, let’s clearly state that for starters.

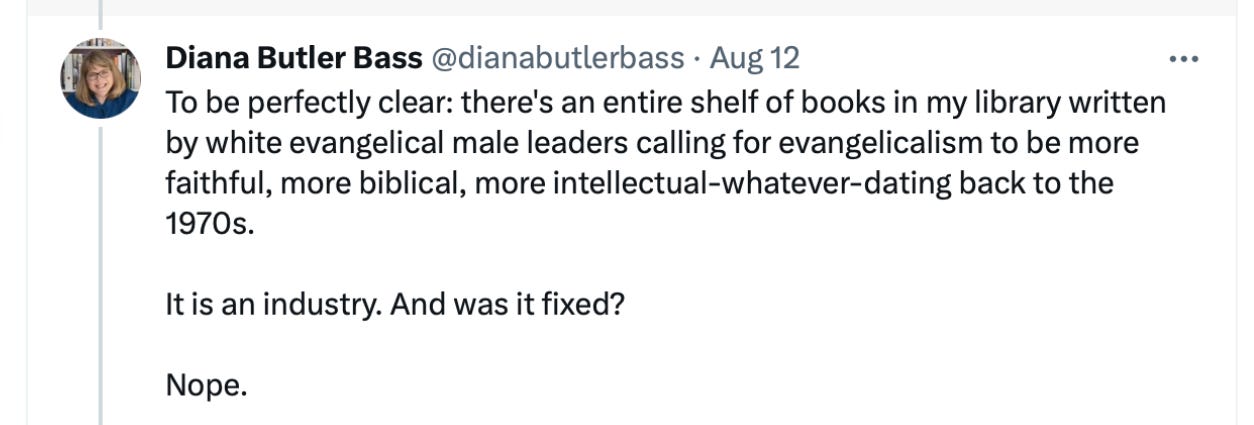

For those who are more fundamentally disheartened with evangelicalism than Russell Moore, please check out the work of Brian McLaren, Diana Butler Bass, Rob Bell, Peter Enns, Rachel Held Evans. You can abandon evangelicalism IN ITS ENTIRETY and remain a Christian. You can get off the crazy-train-roundabout once and for all.

You can lose this religion for real and for good.

On target. I left the Evangelical fold in 1989 after seminary and was ordained in the United Church of Christ. While it was the open social stances on LGBTQ issues, racism an ordaining women that attracted me, it is really the inerrancy underneath that was intolerable and driving the social outcomes. To extend your poison analogy, if you pour chemicals on your farm for years, it won't stop being toxic when you stop. You must learn a new way of farming that respects the earth. Inerrancy is the Roundup in the garage. Just don't use it.

Nailed it. Thank you for saying so clearly what I’ve been trying to put into words. I too have been uplifted by Moore, and French and others, but felt they were missing something, and it’s the inerrancy. I used to mistake my certitudes for faith, and once I let them go and learned-still learning-to walk in the “I don’t know”, I discovered a much deeper faith that I can’t quite describe with words. Beautifully written. TY.