I’ve had a few posts in my head about things I’ve read and watched lately, but then I realized they are all basically the same post about the same thing, something that has affected us all, particularly the last several years, whether we have personal experience with it or not, whether we know it or not.

Myopic, rigid, manipulative faith. It destroys lives. It can destroy whole societies.

1.

I watched Under the Banner of Heaven and then read the book, because I guess I just can’t get enough of religious-fanatic-true-crime. Which is a whole genre. Because, sadly, there are enough cases out there to make a genre. Which is kind of the point of this post. Anyway. If you haven’t seen/read it, it’s the true story of a Mormon family split over some of its members going off the fundamentalist-deep-end to the point where they murdered their brother’s wife and baby, who they saw as heretical enemies to the true Mormon religion (the wife’s real sin was being a smart, spunky woman who kept her husband out of a dangerous cult. Well, a more dangerous one).

These guys' reasoning stemmed from the original Mormon scriptures and revelations, as given to Joseph Smith, which made polygamy (for men only) a central tenet of the faith. Smith, Brigham Young, and most of the early Mormon leaders had multiple wives, including underage girls. Because this practice put them cross-ways with the US government and risked the church’s legal destruction, in 1890, Mormon leaders issued a manifesto that basically said, Oops, Joseph Smith--who was right about everything else and not at all a liar or charlatan--was wrong about that, so stop doing it. The LDS website explains that the manifesto resulted from the government’s dogged persecution (it kinda skirts the whole child abuse/sex slavery thing) and from the Lord revealing His will “line upon line; here a little, there a little.” Interesting, since Joseph Smith just presented those tablets as a wholesale sort of deal.

Mormon fundamentalists then and now have a problem with this course correction. But really, theirs is probably the more intellectually honest and consistent position to take. If you believe God gave this random dude these special gold plates—which he immediately lost--but not in front of anyone else who might verify the story --with all kinds of revelations on them that all the dude's followers take as 100% truth, why would this one provision not also be true? It seems very arbitrary and convenient to be like, ALL THIS STUFF IS TRUE but not that really gross illegal bit that the guy who told us all the other stuff is true said was really, really important. It’s an interesting distinction in a faith the mainstream of which is pretty fundamentalist (i.e., they adhere very closely to a literalist view of a written scripture). But I (only slightly) digress.

2.

Then I read/listened to Timothy Egan's A Fever in the Heartland, which is about the rebirth of the KKK in the 1920's, particularly in Indiana. The Klan's return was built upon a more "equal opportunity" bigotry that included not just Blacks, but Jews, Catholics, and immigrants of various kinds (how very liberal of them). Membership was also a lot more public and respectable than it had been after the Civil War. The Klan's rolls included the politically powerful and connected, religious and civic leaders, even high-level politicians. That's how we got images like this one, of the Klan openly marching by the tens of thousands down Pennsylvania Avenue:

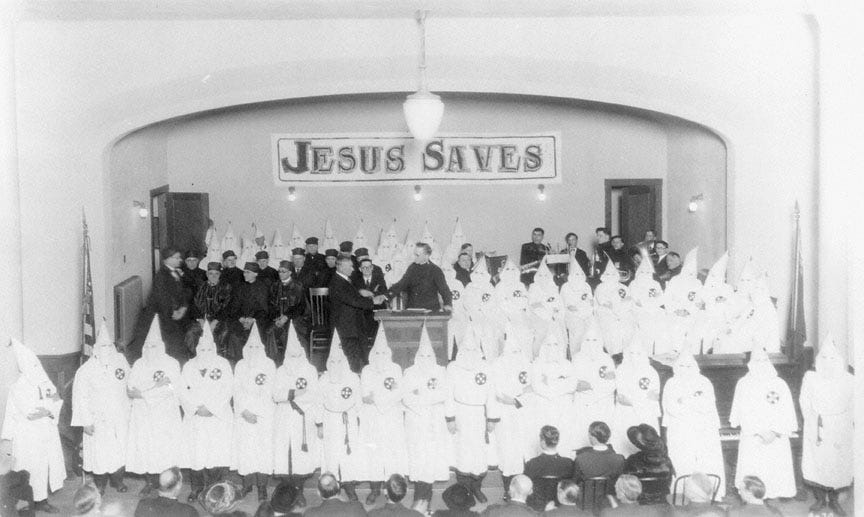

The 1920's Klan also linked racism to a fear of modernity and a fundamentalist Christian faith. Society was rapidly changing; this was the decade of women's suffrage, flappers, the automobile. Even Fundamentalists’ big legal victories of the 1920’s—Prohibition and the Scopes trial—belied their cultural decline and were soon erased by the tides. To underscore and strengthen its racial appeals, the Klan routinely appealed to Americans' religious fears and sensibilities, promising to take the nation back from modernists and non-Protestant Christians, and it used its political power to install leaders who pursued this aim. And that's how we got images like this one:

Let me pause right here and ask you DOES ANY OF THIS SOUND AT ALL FAMILIAR? No? I guess it’s just me.

What I didn't realize, but should have assumed, was how much of a culture of abuse and corruption pervaded the Klan. Egan focused most of his book on the Grand Wizard of Indiana, David Stephenson, and his reign of lawlessness and violent crime. He was a brutal, serial rapist who was eventually convicted for murdering one victim who drank poison in attempt to escape a lengthy and tortuous detention. While "Steve" preached conservative Christian values (the "family values" celebrating the "traditional family" in today's parlance), behind the scenes, he lived a life of pure hedonism and license. He took the Klan's subjugation of women to its logical conclusion.

Again, DOES ANY OF THIS SOUND FAMILIAR.

3.

Now we move around the world to my home country of Kenya. And just for context, since independence in 1963, Kenya has become a full-blown, American-style Bible belt. 85% of Kenyans are Christians, 60% are Protestants (half of those are evangelicals), and only 1% of Kenyans say they are not religious. And unlike many Americans who claim to be Christians, Kenyan Christians attend church at a high rate (although Covid did eat into that, which everyone is quite angsty about). Kenya's politicians very showily go to church and tout their evangelical faith (while stealing public funds, but I’m sure Jesus would want them to have it). There are mega-churches galore and a strong anti-gay movement (a Uganda-style law criminalizing gay sex was recently introduced in Parliament). What can I say, American missionaries like my parents did a really great job importing American-style Christianity built on an "inerrant" view of scripture.

And just like in America--I also just watched the documentary about Bill Gothard's "quiverfull" movement, ugh and eww--there have been numerous cases of exploitative and abusive religious leaders who have taken advantage of the devoted. But this year, the worst case of them all has been uncovered in forest near the Kenya coast called Shakahola. It’s like Kenya’s own Jonestown.

Paul Mackenzie Nthenge (who has no theological training that I can tell) started his ministry in 2003 claiming to have direct revelations from God about Jesus’s return and the evils of modernity. In 2019, he moved his flock out of an urban area to the forest, telling followers Jesus awaited them there. When they arrived, they didn’t see Jesus, so he guided them into ever more strict devotion which he promised would hasten Christ’s return. Earlier this year, he told them to fast and pray, abstaining from all food and water. The children died first, followed by hundreds more. 240 bodies have now been found; hundreds more are missing. Many of the bodies show signs of suffocation and strangulation. Nthenge has been charged with murder.

***

I've heard my parents and other American missionaries/Christians familiar with Africa bemoan the rise there of suspect Pentecostal movements that too easily bleed into cults or become slush funds for con men and women. They often talk about it as if those societies are particularly prone to such things, due to their supposed resemblance to traditional African religion, with its superstitions, and the lack of good theological training. That's a big reason American missionaries need to be there, goes the rationale, to prevent this kind of destructive belief.

I find this a little too convenient (and rather condescending to Africans). It completely ignores not only the prevalence of extreme Christian cults and other examples of toxic Christianity in the US, but a lot of common ideological and religious beliefs these strains share with more mainstream American evangelical Christianity.

To be clear, I am not a theologian. But I have been steeped in evangelicalism my entire life. Which is not necessarily unhealthy. I myself did not benefit from that particular form of Christianity, but I know many people who have. My point here is not to bash evangelical Christianity. My point here is to show how some of the central tenets of that faith can easily slide into something destructive. Or actually how one particular tenet--inerrancy--does that.

In modern, non-religious human life, we have many tools to help us determine what is good and true and healthy:

We have our instinct, our "spidey-sense" if you will. Granted, some folks have better instincts than others, but I think most of us have had the sense of "something ain't right here." In the moment, it might be a raised pulse or racing heart. If we are in a more chronically bad situation, it might be a knot in our stomach or a sense of being off-balance emotionally.

We have science. We can run tests and do unbiased, double-blind studies. We know, for instance, that smoking is really, really bad for you. We know that vaccines are safe and effective. While it's more difficult to design studies on social scientific questions, we have nonetheless learned much about human relationship, mental health, and childhood development. It's pretty clear, for instance, that abuse has long-term impact.

We have democracy, institutions, the rule of law, and a sense of fairness that has formed over many centuries. While "the people" are clearly not always right, we have a system that, when it works well, is supposed to militate against possible foolishness and be a neutral arbiter between people. Even in countries without well-formed government, there is a sense that we need some kind of government to ensure some kind of order and fairness. And it's pretty clear from a long view of human history that a system of government that gives people freedom to live how they choose, as long as they aren't hurting others, is most conducive to human thriving.

We have our ability to think rationally and critically, to seek out and weigh differing information, to learn from our experiences, and to observe the results of actions.

Having these tools does not mean judgment is easy. Many (most?) of our choices are not clear-cut. We make bad choices we thought were good, and good choices we feared might be bad. Life is so very complicated, and we are going to make mistakes. Nothing is fool proof. Ultimately, we learn by doing. We walk by faith, not by sight.

But that's exactly the point.

That's exactly why we don't have authoritarian government. And that's exactly why a belief in an "inerrant" scripture is potentially dangerous.

Such a belief system seeks to make the complicated simple. It outsources the complex, uncertain, human process of making choices and grappling with difficult questions and finding life's meaning to a single, concrete, external authority--The Bible (or in other fundamentalist cases, The Book of Mormon or the Quran).

And not only the book itself--hey, there's a lot of great stuff in the Bible! I'm not even disputing its divine inspiration--but a single, unambiguous interpretation of what it means and how to apply it. One that does not take into consideration all the other tools God has given us over the vast expanse of human history--things in our biology and brains and societal development and scientific advances. One that doesn't even take into consideration the many, clear cases of those authorities' interpretations being catastrophically wrong. See, Joseph Smith and the KKK-supporting pastors.

(Also, not for nothing but the authority to interpret scripture has overwhelmingly resided with a certain group of people, i.e. men, and most often white men. The people who happen to have held almost all power and reaped all earthly reward in human societies for almost all of our history. They know best for everyone. How convenient for them as they strive to maintain their position.)

In my own non-cult life (well, some would dispute that designation), I have been harmed by this outsourcing of authority and thought and judgment, and I nearly made a very bad decision that would have altered the entire course of many lives.

That decision point was made necessary by a previous one that was likewise guided by these beliefs. I got married to someone I didn't love at a young age, which was probably mostly just pure, youthful stupidity on my part, but it definitely was influenced by evangelical teachings that 1) love is a commitment, not a feeling 2) marriage between two Christians is always a great thing and 3) sex outside of marriage is life-destroying (so maybe you should get married asap). I was told that these ideas were absolutely central to being a Christian as determined by scripture.

So, I ignored the nausea I had in romantic situations with my husband-to-be. I ignored the clear indications that I was not thriving in the relationship. I ignored my rational thought about why he wasn't who I needed to be with. I ignored the revelations of the pre-marital counseling we did (although it was evangelically-based and mainly focused on getting us married anyway).

After seven-plus years of badness, I almost didn't get divorced because I was told the BIBLE IS CLEAR that that was simply not an option for any Christian. I hung in there as long as I could based on that teaching (and some other pithy add-ons, my favorite of which is “God wants us to be holy, not happy." Put that on a T-shirt), I ignored my own mental health, the indications that the relationship grew more and more toxic for both of us, and just plain logic (we didn’t have kids or property, a pretty easy split). As one friend who urged me to leave said, "Why should two people be miserable when potentially four people could be happy?" I eventually followed my gut and my head and I left, and that is exactly what happened. Twenty years later, there are four of us who are happy (like as two separate couples, just to be clear), two children exist who wouldn't otherwise, and two other children have been adopted into a secure and loving home.

So what does my marital history have to do with cults? Well, similar dynamics are at play in those contexts. People are taught to shut down all other thought processes and submit their thinking and their choices to an external authority. Who definitely doesn't have all the information about their lives or all the answers about life in general and may or may not have their interests at heart.

In more benign cases, people like me may be shamed into staying in bad but non-abusive marriages. Or told we can't read certain books that we would really love or we should avoid certain types of people from whom we might learn or abstain from really delicious wine. In more severe cases, people are forced to stay in abusive marriages or told they can't live as their authentic selves.

And in extreme cases, people fall under the sway of sociopathic leaders who manipulate the human desire for certainty and clarity and human fears about change or difference for the leaders’ personal power and gain.

And in the worst of those cases, these leaders stoke that anxiety into movements that aren't content to control merely a group of followers but rather turn on society writ large, reject the rule of law and democratic norms, and attempt to project their beliefs and authority by force.

Human history is littered with such leaders and movements and cases. American-style evangelicalism has spawned many and continues to do so. As a country, we are right now in real political peril as a result.

God help us.

For more on this topic:

What Makes the Church Uniquely Corruptible

I've known one (almost certain) murderer in my life, and he was a missionary. I won't go into the details here--the case was never subject to any legal system, and therefore there is no way to prove it--but it was widely assumed in my circles that he was indeed guilty of that crime.

Amazing stuff Holly. I am glad you took that scary jump, and are sharing it with us

Thanks again, Holly. I'm so sorry that you had to go through this, although you certainly seem to have come through it as a vastly better human. Signed, a lapsed former Evangelical whose parents thought that attending Billy Graham crusades was a great recreational activity.