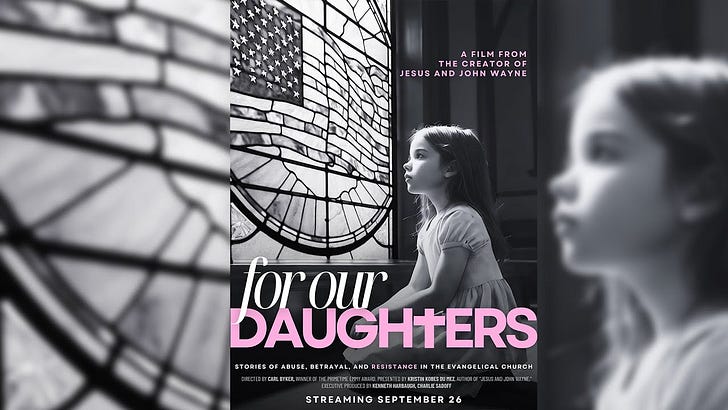

Kristin Du Mez, author of the best-selling Jesus and John Wayne, has produced a short documentary, For Our Daughters, which tells the stories of survivors of abuse within evangelical churches (and actually, all of the cases profiled in the film happened in Southern Baptist churches).

In explaining what motivated her to make the film, she said1 that so many women in that world, including pastors’ wives and people who towed the line outwardly, contacted her after her book came out to thank her for shedding a light on the toxic gender ideology of white evangelicalism. They told her it was “too late” for them to leave or to speak out forcefully, as their lives were too tangled up with that of the church. But they prayed for something better “for our daughters.”

The film tells the stories of Jules Woodson, Tiffany Thigpen, and Christa Brown, with contributions from Rachael Denhollander and Cait West. I was familiar with all their cases (and so many more), but had never seen them speak on camera. It’s a powerful film, and it speaks to the roots of the abuse crisis in white evangelicalism. Please watch, share, and speak out.

The film covers well the link between the abuse crisis and women’s subjugation within evangelical culture and references its deeper theological roots. But I’d like to foot stomp a few points on that score.

First of all, it’s important to spell out why this is a CRISIS, a systemic issue, and not “a few bad apples” who either “slipped” or who “were never really Christians.” Every human society and institution and community, religious or not, includes people who will harm other, weaker members. And therefore all settings will have some abuse.

But abuse becomes systemic and widespread when there is no reliable, consistent accountability. Not only are the worst of the “bad apples” free to continue offending over and over, other, less sociopathic people with social power will get the message that they, too, can get away with abuse, exploitation, and corruption. And so the problem mushrooms.

And that is what has happened in American evangelicalism. I’ve lived and worked in secular contexts and I’ve lived and worked in evangelical ones, and there’s just no comparison in my experience in terms of systemic problems. White evangelicalism has a massive, massive issue. The main difference has been how well that culture hides and justifies its sins.

Kristin’s film details one reason why: patriarchy, where male authority runs rampant and women are conditioned to submit to it. But of course, there are male victims of sexual and other abuse in evangelicalism, too (usually children, who are always the most vulnerable). And those perpetrators have often gone unchecked as well, despite the evangelical revulsion toward homosexuality. One of the most egregious cases was at the largest Christian camp in America, Kanukuk, as uncovered by Nancy French.

I’ve written before about what makes the evangelical church uniquely corruptible and how a culture of collective narcissism prevents evangelicals from acknowledging their failures. They view themselves as the Good Guys in a black-and-white heroic narrative. Abuse just doesn’t fit that story.

I won’t rehash those posts, but instead beat another favorite dead horse of mine, inerrancy. Quick review, inerrancy is a pretty modern, especially (but not exclusively) American doctrine, that solidified in the 19th and 20th centuries in response to modernist and scientific arguments that challenged traditional religious authority and the broader status quo. Inerrancy asserts that the Bible is the perfect, final authority on, well, everything, and that its interpretation should strictly adhere to the text as written without regard for the time and place in which it was written.

Inerrancy was invented for two reasons 1) to shore up conformity and power within evangelicalism so that 2) it could better defend against perceived external threats from the broader culture as its own influence slipped.

On the first score, inerrancy has worked spectacularly to police dissent and fortify existing (white, male) power structures. In fact, I had a great conversation this week with Isaac Sharp, whose book The Other Evangelicals details how multiple groups of evangelical dissenters were labeled heretics and chased out using the cudgel of inerrancy.

Inerrancy has helped consolidate power within—even in evangelicalism’s rather diffuse, flat institutional structure—by creating an authoritarian culture, in which people are not encouraged to think for themselves, debate is suppressed, there are unequivocal “right answers,” certainty on all matters is both possible and mandatory, and—this is really, really key—correct DOCTRINE is prioritized over correct ETHIC.

ETHICS are squishy. They are general principles for living. Ethics involve walking towards a destination without a defined path. DOCTRINE is rock solid. It’s a paved super highway with no exits.

On the second front, inerrancy is an attempt to preserve evangelicalism’s power vis-a-vis the larger culture by clinging to absolute certainty in the face of growing pluralism and ambiguity. Inerrancy fosters cultural tribalism, a sense of, “We are right and everyone else is wrong.” The implication is, we deserve cultural and political power because we have the answers to society’s problems. It’s Us vs. Them, the Saved and the Lost, the Upstanding and the Vile.

Evangelicals can’t afford to be wrong, because it’s too central to their identity. There’s a sense that evangelical Christian beliefs are right not only by virtue of a correct interpretation of the Bible, they prove themselves to be right in practice. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard a version of this spiritual prosperity gospel—we have the best faith and make the correct moral choices and our lives and families and schools and institutions demonstrate that. Anything “Christian” is superior. You look for that Jesus fish on everything from business signs to colleges to movies to music to counselors.

So if it turns out some of your leaders and spiritual heroes are monsters, well, that wrecks everything. It wrecks their authority—their ability to maintain order within—and it wrecks the group’s credibility within the larger culture—its ability to impose order without. And if victims go to the police, it introduces outside authority. On all fronts, it wrecks the tribe’s entire self-concept and its ability to maintain that.

So things get swept under the rug—abuse, racism, corruption, scandal, failure. The stories of people that don’t reinforce the tribe’s narratives. History itself. 2

You either ignore those stories completely, or you compartmentalize them. That happened over there and is/was bad. But that’s just one bad person/idea/belief/practice/chapter/episode. It has no bearing on the whole, like how that one cringe episode of Ted Lasso where Beard has a weird night in London has no bearing on the brilliance of that show.

The last point I’ll make about inerrancy on this score is this: If you are deriving your ethic from an attempted literal interpretation of an ancient document, you should really not be surprised when the results tend toward misogyny, abusive power, authoritarianism, and tribalistic thinking.

For the various times in which its books were written, the Bible is actually quite progressive, and you can clearly see a moral evolution in its pages. Jesus’s teachings were revolutionary then and now, but they are also the most abstract. Jesus very rarely deals in specifics (which is probably why fundamentalists don’t seem to spend a lot of time dwelling on them). But all the Bible’s authors were influenced by their culture, just as all humans are, and all of those cultures were way behind our own day.

As I have said before—What do folks think God has been doing for the last 2,000 years? Repeatedly binge watching Downton Abbey?

Since the Bible was written, we’ve gotten ourselves democracy, human rights, constitutions, religious freedom, affectionate parenting, marriage based on love and mutuality, social mobility, coffee and elastic waistbands.

And I for one think those things are divine revelations.

I was supposed to spend last week in Akron, Ohio celebrating the 25th anniversary of MK Safety Net, an organization founded to improve mission field accountability and advocate for missionary kid (MK) survivors. Sadly, I wasn’t up for the trip after Jana’s passing.

These folks are incredible people. I can’t wait for you to hear more about them in my book, for which they were essential sources. Especially two of the founders Dianne Darr Couts and Richard Darr, siblings who were horribly abused my multiple missionaries when they were growing up in West Africa. I can’t put into adequate words how much I admire them.

As a child, I got glimpses of how the evangelical propensity to hide its dirty laundry was particularly pernicious on the mission field. But in researching my book, I sadly discovered I didn’t know the half of it.

In addition to the cultural and theological forces that foster abuse in American evangelicalism at home, there are additional factors on the mission field that come into play.

In evangelicalism, missionaries are close to saints (and to be clear, most of the many missionaries I have known are good people. Nothing close to saints, however). And missions are seen as the highest form of Christian calling. As my book details, for 200 years, missions have been central to the construction of a grandiose American evangelical narrative. So mission field abuse is particularly threatening to the evangelical self-image. There has been strong incentive to cover it up, although there have been many good changes over the last 15 years.

Covering it up has been easy to do, given the context—often countries with weak rule of law, high tolerance for domestic and child abuse, and usually high regard for relatively wealthy, privileged American missionaries. In many countries around the world, missionaries are not peers in their communities, and they aren’t subject to the accountability of community relationships and institutions.

And before 2003, there was no US jurisdiction for crimes committed by Americans overseas. Now there is some, but given the difficulties of reporting, investigating, and successful prosecuting sex crimes even here in the US, the legal hurdles for overseas accountability are significant.

MKs have suffered, and probably many locals, too, although we’ll probably never know in most cases. One thing advocates will tell you is there’s almost never just one or even a few victims. And local women and children in many countries have few protections to begin with. They are easy marks.3

It’s important that we talk about these things. It’s important for survivors, who have too often been ignored at best, viciously attacked at worst. It’s important for those who haven’t been abused yet. Maybe they won’t have to live lives of survival.

And it’s important for the American church. Those who are speaking out seem to many evangelicals as bullies who are piling on. But believe it or not, we are trying to save you from yourselves.

If you don’t finally face the full extent of your failures—and yes, that includes taking a hard look at your theology and your most cherished enterprises and institutions—and yes, that includes the “good,” non-MAGA evangelicals—your faith tradition4 will not survive. And the way things are going right now, it may bring American democracy with it.

And it won’t be “the world” that has defeated you. You will have done it to yourselves.

So thank God for these survivors and journalists and advocates. They are your friends. They are offering you a path out the wilderness, one of humility and repentance. Please, take it.

And please, drive a stake deep into the heart of inerrancy, with its legacy of slavery and violence and hurt and harm and abuse and corruption and ashes.

I can’t remember where exactly I saw/heard/read her say this because middle age.

I’ll add that white evangelicalism’s increasing self-isolation in a makes it easy to evade external sources of accountability and to control narratives.

Here’s one case that was successfully prosecuted by the US Justice Department thanks to the dogged efforts of a Kenyan American woman.

I’m not talking about Christianity in general. Certainly not faith in general. God is bigger than the American evangelical church, or, in my opinion, Christianity.

Oh Holly! You nailed it. The connection between inerrancy and abuse is so clear, now that you say it. Thank you!!

Ugh, I feel like such a fool for supporting an American pastor whose orphanage director in the Philippines was accused of sexual abuse. All because my parents met the American and swore he was a great guy. Now it seems likely that the abuse was swept under the rug. Infuriating on many levels.