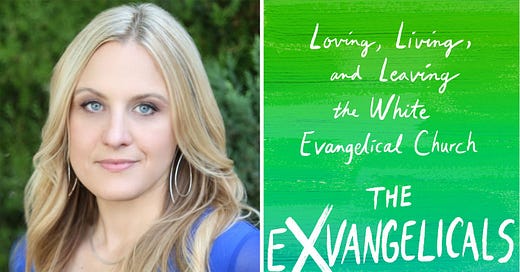

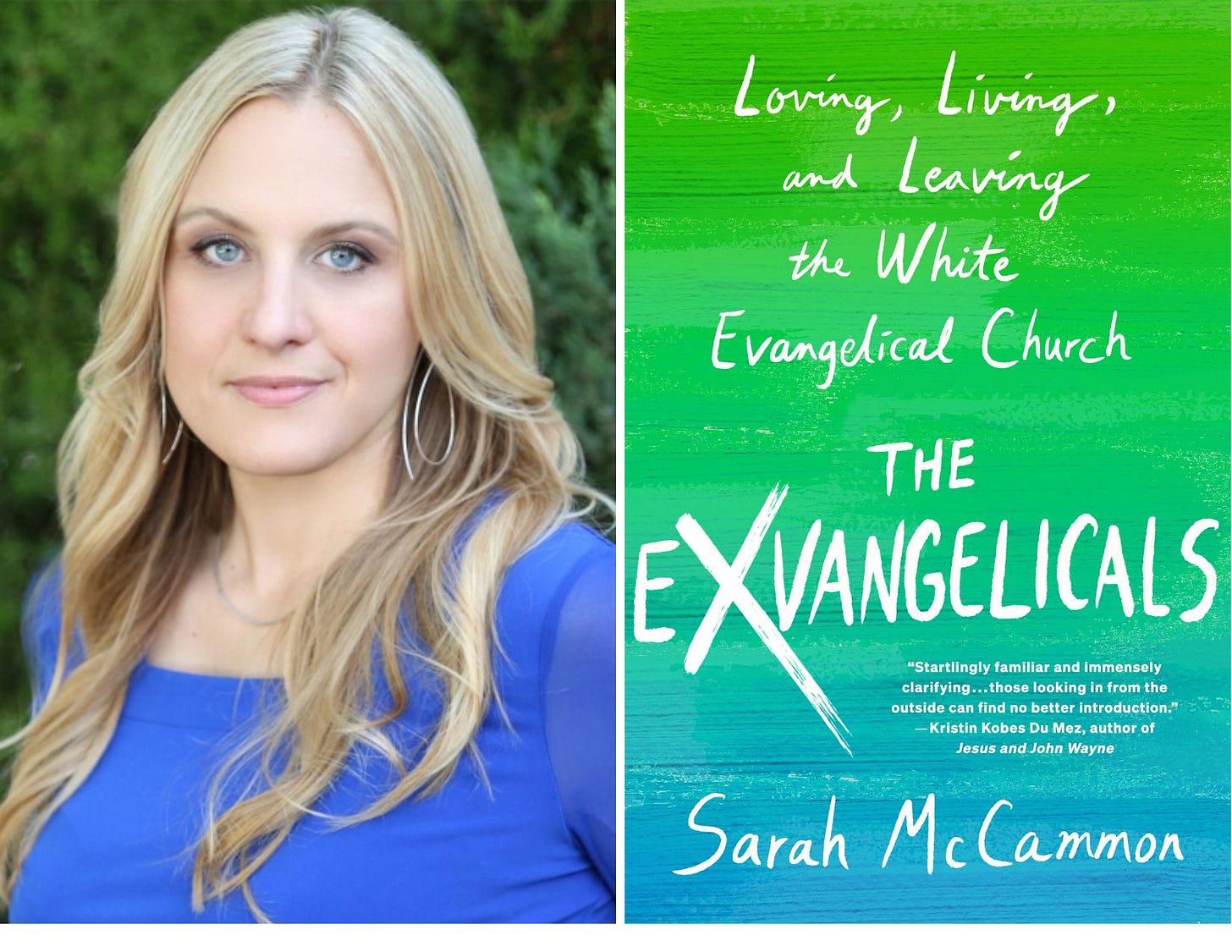

Q&A with NPR's Sarah McCammon about her new book The Exvangelicals

I was one of her many sources and got to read it early!

I was so thrilled to hear that Sarah McCammon, whose work on NPR I’ve enjoyed for years, was writing a book on people who had grown up evangelical but chose to leave as adults. I was even more excited when I realized that she was one of us! And I was grateful to share a lengthy conversation with her after I reached out offering to be a source. We have so much in common, and to me, our chat seemed less of a journalistic interview (though she did ask excellent questions like the outstanding journalist she is) than sharing between empathetic friends.

Sarah grew up in the midwest going to a pretty fundamentalist church and attending a private Christian school and an evangelical college. And though I grew up half a world away from her, our childhoods were remarkably similar, because one of the misunderstood facts of the mission field is that, at least in my experience, it’s as much like living in an white American evangelical bubble as it is a truly multicultural experience. Certainly my evangelical mission-run boarding school in Kenya and Sarah’s private Christian academy in Missouri had many similarities, from the female-modesty-obsessed dress code, to the hardcore purity culture messaging, to the “colorblind” take on American history and culture, to the dichotomous “Us vs. Them” view of the world and secular culture, to the enormous pressure we felt even as children to save every lost soul. For both Sarah and me, the fear of hell, for ourselves—what if my faith wasn’t sincere enough? How could I be sure?—and others for whom we felt responsible was something that left lasting scars.

I found myself nodding and laughing in recognition as I read. Or just because evangelicalism can be simply bananas. I spit my wine out over Sarah’s mom telling her, “If you have Jesus, you don’t need oral sex.” (I wonder if the opposite is also true?)

I also deeply related to Sarah’s exit from evangelicalism, as well as the many other stories of exit and broader research on America’s un-churching with which she contextualized her own story. For many of us, it took surprisingly little to begin unraveling a tightly woven faith that was much more than that, it was a culture, a way of life, and entire system of belief, the contradictions and rigidity of which mean it often doesn’t survive first contact with the outside, secular world (or just too much thinking). In fact, that’s why so many evangelicals have increasingly walled themselves off into an insular subculture.

For both Sarah and me, loving and seeing the goodness of people who wouldn’t make the heavenly cut according to narrow evangelical belief was a major factor in our exits. So were our divorces, after “doing everything right,” following evangelical guidance on dating, sex, and marriage, then failing to reap the promised rewards. Her email to her parents telling them she was getting divorced and their response was nearly identical to my own experience. I, too, emailed my parents with the news, because I couldn't bear to have a conversation. She loved her gay, atheist grandfather, whose salvation Sarah’s family earnestly prayed for every night, just like my family prayed for my non-Christian grandparents, whom I adored. Sarah’s account of her relationship with her grandfather and how it evolved with her faith is an incredibly moving microcosm of how and why so many of us have been unable to stay within evangelicalism. Ultimately the people we love, who exist in flesh and blood right in front of us, say more about who God is than ancient scriptures and disembodied doctrines and dogmas.

But having one’s faith come undone is far easier as an intellectual exercise than as a human experience. That is wretchedly hard, as Sarah also details through her own story and those of others, who have landed in various places, religiously, from atheism to ongoing Christian practice. The loss of community, family relationships, the certainty of having all the answers—none of it is comfortable. Given that evangelicalism is such an all-encompassing experience, leaving it is a wholesale unmooring of one’s life. Sarah says she often felt like a “shipwrecked soul.” She’s reclaimed belonging through relationships with people of wholly different backgrounds, through learning to see the world in new and beautiful ways, and in finding peace in uncertainty and letting go. This has been my experience, too.

As much recognition as I found in this book, I think those who are not as familiar with evangelicalism and are wondering what the heck is going on with American Christianity will get the most out of it. Just like all of Sarah’s work, this is rigorously researched and clearly presented through data and detailed reporting. The tone, even when relating her own story, is as objective as possible, even, fair, curious, and compassionate in a way that is an example to me as I finish up my own book. After reading this, I can see I have a bit more work to do in presenting the nuances of a faith experience and achieving a respectful and kind tone. You’ll see in the Q&A below, in fact, that she didn’t even take the very tasty bait I laid out! Which I respect, but honestly found a bit frustrating :)

So go read this book! It’s out on March 19. And enjoy this Q&A that Sarah generously agreed to do.

You relate some very painful experiences here, so let me say first that I am so sorry you went through those things, some of which I can relate to and some of which I escaped (then of course, I experienced other bad things that you didn't). It's so interesting how the same teachings can work out in different ways--for example, my parents were big Dr. [James] Dobson [of Focus on the Family] proponents but I only remember getting one spanking, and it was more humiliating than physically painful. Then of course, we both know people who have had truly joyful experiences in evangelical culture, beyond just the belonging piece. Is there anything that you've noticed that accounts for this variation, or is it just a matter of individual personality and family dynamic?

It’s something I’ve wondered about myself. I suspect you’re right - we each come to experiences with our particular backgrounds and internal wiring, and everyone responds to trauma differently. I’m not here to judge people who find fulfillment and peace within the evangelical world - but I do hope my book will help them to understand the many who don’t. I’d also point out that there’s a large, longstanding, and growing body of evidence supporting the idea that spanking children does more harm than good.

There's a class of "enlightened" evangelicals out there (Russell Moore being one, David French, Beth Moore, Peter Wehner etc.) who have been highly critical of the movement in the wake of Trumpism, but generally haven't changed their fundamental beliefs. Russell Moore, in his book, doubles down, at least in passing, on inerrancy, for example. Or--I attended a PCA church pre-2018 that would fit this category (not at all Trumpy, pretty racially enlightened, but still inerrantist, still not LGBTQ affirming, still pro-spanking, still no women ministers, etc). Do you think there's a way to "salvage" evangelical Christianity or are the fundamental beliefs (such as inerrancy) destined to produce toxic fruit?

I can only speak for myself, and that’s what I’ve tried to do with my book. I don’t know that I’m in a position to pass judgment on those bigger questions. The purpose of journalism, of sharing stories, is to shine a light - and I believe the old adage that daylight is the ultimate disinfectant. I am pleased to see some evangelical leaders thoughtfully grappling with the tradition. But I’ve never wanted to tell people where their personal journeys should land.

Honestly, to see it all laid out like this in your book--it makes me think white evangelicalism really is a cult, an assertion I have generally rejected. What do you think? Why or why not?

This feels like a question for a religion scholar, and I try to stick to journalism. This isn’t a dodge, it’s just not what I do. I can see why some people would view some evangelical churches as cults. But I don’t think a fair assessment of all of them. Evangelicalism is such a vast movement that there is a tremendous variety of belief and practice within it.

What do you think is the enduring appeal/power of white evangelicalism? It's very American, and yet it's been exported around the world and is booming in places like Africa even while it fades in power here.

A lot of it ultimately goes back to a sense of meaning, purpose, and community. I think those are things that humans naturally desire, and churches often provide them, whatever the ideology. Evangelicalism is also particularly effective in that it’s versatile and, you could say, scalable and iterable. It’s been notoriously difficult for pollsters and scholars to define because there is so much variety, and no official hierarchy or doctrine (although there certainly are organizations within the movement that have their own hierarchy and doctrine, such as the Southern Baptist Convention). So by its nature, the movement can easily be exported and adjusted to the particulars of various communities.

As for most of us, your journey out of evangelicalism seems like it was pretty gradual ("beads on a string" I think you said) but mainly influenced by your friendships with non-Christians (once you were able to have some). For me a big obstacle was figuring out what to do with the Bible/getting over "inerrancy." How did you reckon with that? What's your view of the Bible now?

The more I studied the history of how the Bible was put together, the less I felt the need to try to cling to inerrancy. I see the Bible as a beautiful and important document and I often feel moved and guided by it. I’ve also benefited from observing my husband’s Reform Jewish tradition and the scholarship with which his rabbis have approached scripture. It feels like a different but still deeply reverent approach, and one informed by a study of history.

You seemed to be a true believer growing up--looking back, do you think you really were or was it mainly fear-induced? Did you ever have the religious experience many evangelicals proclaim (did you feel "close to God"/did you feel like you had a "personal relationship" with Jesus)? Is there anything about your faith back then or the culture surrounding it that you kept and still cherish? Anything you gave up but still miss?

I certainly wanted to feel close to God, and I wanted to live my life in the right way. I struggled with the idea of a “personal relationship.” I would pray and ask God to guide me and lead me, but I never confidently felt like I was hearing from God. But I don’t think that was unusual. I remember hearing sermons about “how to hear from the Lord’ and it was clear to me that other people struggled, too. The advice usually came down to things like: read the Bible, get advice from pastors and trusted Christian friends, wait for a feeling of “peace” in your heart, and look for circumstances through which God might be guiding you - wait for “doors to open,” as people sometimes said. Nothing extraordinarily mystical. So it made me think there must be a lot of other people in my evangelical community who found this “relationship” to be as elusive as I often did.

There was so much fear, and a lot of guilt and shame around what I felt or didn’t feel. The pressure to experience a certain type of emotion or get my mind around a set of ideas that didn’t seem obvious and often didn’t match my intuitions seemed to get in the way for me. Today, I would actually say I feel closer to God, in some sense, and more comfortable with prayer than I did as a child - even though at that time I would have said I had a more specific set of theological commitments.

You include some beautiful ways exvangelicals are finding community and belonging outside that culture, including your own experience with your husband's Judaism (so lovely). They seem to boil down to getting to know yourself in a new context (or maybe for the first time, fully). It makes me wonder if it's even possible to really know oneself within a tribal, restrictive culture like evangelicalism. Are there non-religious contexts that function the same way/discourage self-knowledge? In the search for belonging, what's the balance between serving the needs of the group/conformity and individuality?

Wow, these are great questions but huge, philosophical ones!! I’d love to sit down with a book club and hear what other people think. I don’t think evangelicalism is uniquely susceptible to groupthink or tribalism, no. I think those are human tendencies that religion sometimes encourages but are not exclusive to religion. But you really need an anthropologist for this one, I think! And a good book club!

Looking out into the world of exvangelicalism, I seem to be in a minority of folks who have moved to a mainline church vs. leaving organized Christianity altogether. I wonder why more people leaving evangelicalism don't go in that direction. I have my own theories, but what are yours? Is there something mainline churches could be doing/saying to appeal more to exvangelicals?

I’ve spent time in mainline churches - Episcopalian in particular - and I’ve benefited from that. When I was first venturing out in my early 20s, I was often one of the youngest people in the room at these churches; evangelical churches, on the other hand, have largely done a great job of having small groups and childcare and all sorts of resources designed to welcome people and connect them at whatever stage of life they’re in. This is particularly true for young families. I also sometimes felt like a fish out of water trying to understand the liturgy - which was gorgeous but very different from the overhead projector worship songs I’d grown up singing. I think some mainline churches could do a better job of welcoming people who are unfamiliar with those traditions. And some of them need to update their websites!

I think a lot of people have family relationships that are difficult to navigate across different strong belief, whether that be political, religious, or ideological. How do you handle these dynamics?

The answers are different for everyone, depending on their personalities and dynamics. For some, there’s estrangement. But more often, at least anecdotally, I hear about people having to set explicit or implicit boundaries around their relationships. Certain subjects are off limits or just don’t come up.. As I discuss in the book, some of the people I interviewed have made peace with their families in unique ways that may seem painful and tedious, but preferable to no relationship at all.

Lastly, can you help me answer a question I've wrestled with for so many years--Why is Christian pop music (and other pop culture) so awful? Like, there's some talented people in that space but most of it has this kind of sound that I can pick out without even hearing the words. What is that?

Ha! The short answer, I think, is that so much of it is derivative and sounds like an attempt to copy “secular music” while adding stuff about Jesus. But it’s not all bad! I still love Amy Grant!

I also love Amy Grant, by the way. Amy Grant is universal and forever.

I was very blessed (no pun intended) to have been raised by very progressive parents in 1970s Texas, no less! My mother went to Presbyterian services regularly, my dad abstained from organized religion entirely. But they encouraged me to attend different churches with friends and neighbors, and see what spoke to me. I did exactly that, and it turned out to be Buddhism that gave me the most peace and comfort. After my mother died from cancer when I was 12, I was so angry at God for taking her away from us. It was discovering Buddhism and karma at 15 that helped me turn back to God. And even though I think Jesus is my favorite teacher, it's Buddha that was my greatest one.

I can't imagine what I would be like today without my parents' amazing gift to me. And the bravery you have inside to leave such a frightening institution... wow! You truly are inspiring, Holly, and I'm rooting for you all the way!

Sarah was featured on this mornings Sunday Weekend edition. I am so tired of the Christian right. I understand the desire to avoid the temptations of the flesh, we were taught that in Catholic school too - also about female modesty. But I grew up in the 1950s and 60s. I don't see how kids can be isolated from the internet. Even TV ads show frank displays of underwear, of erectile dysfunction etc.

In the choir where I sing, one member home schooled her kids. But now as they live adult lives, they have drifted away. Of course, NJ has a different culture from America's heartland. But I assume that the edifice of Christianity will disappear within a generation.