The first time I heard John Lennon’s “Imagine” as a young evangelical, I was scandalized and indignant. How dare he talk about there being no heaven and hell like that is a good thing! How would people ever behave themselves! Never mind that there IS a heaven and hell whether he likes it or not! And I know where he went! THIS MAN NEEDS JESUS OH WAIT IT’S TOO LATE WHAT A SHAME CAN YOU SAY AMEN.

Now, after studying in history books and seeing with my own eyes the devastation wrought by people who not only believe there is a heaven and hell, they are convinced they know who is going where—I need no explanation. I have listened to that song and wept, over and over, in the last few months.

Imagine there's no heaven

It's easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people

Living for today

If only.

One of the friends I visited in California was Debby Borza, the mother of Deora Bodley, the youngest passenger on United 93. Deora was 20, her whole beautiful life in front of her.

I randomly met Debby about a decade ago when we were seated next to her at a non-profit event. I was immediately drawn to her open and kind heart. Long story short, which I actually wrote about for the CIA’s website, Debby started leading tours of new CIA analysts around the Shanksville Memorial and became a fixture in our training program. She then made the breathtaking decision to donate Deora’s gym bag from the flight to the Agency’s museum.

We were all overwhelmed at her generosity, and honestly, her magnanimity towards the Agency. 9/11 was, after all, an immense intelligence failure. Between the CIA and the FBI, there were enough dots there to connect, but nobody did that, for all kinds of complex reasons stemming from human cognition to bureaucratic structures and systems. The Agency was only able to give the President a pretty generic warning of an impending attack about a month in advance. Certainly nothing he might have acted upon.

My colleagues who were there at the time are still haunted by it. The Intelligence Community was restructured in the wake of it. The Agency’s entire analytic culture, training, and tradecraft was reformed because of it. (Incidentally, in ways that elevated DEI).

Sidenote: This is called repentance. You don’t just acknowledge a wrong, you examine and change the system, practices, and beliefs that caused it. American evangelicalism could take a forking page.

Now that I know Debby well, her graciousness doesn’t surprise me at all. That’s who she is. She isn’t fueled by hate or anger. She only wants people to learn and come away better. She knows Deora’s legacy isn’t served by enduring bitterness.

She asked me to come for a visit so I could look through some of Deora’s many essays and journals in hopes I might have some ideas for her on how to share them with others. So we sat on her couch in Long Beach and paged through pages and pages of teenaged, pencilled handwriting and early 90s computer type. Class essays and private diaries. Girlish drivel and wisdom beyond her age.

Deora was a deep and sensitive soul, much like her mother. Her adolescent confessions of crushes and girl politics toggled back and forth with questions of why we are here, why human beings can’t live in peace, why there is poverty and injustice. “You ask who, what, when, where, how,” she wrote. “I ask peace.”

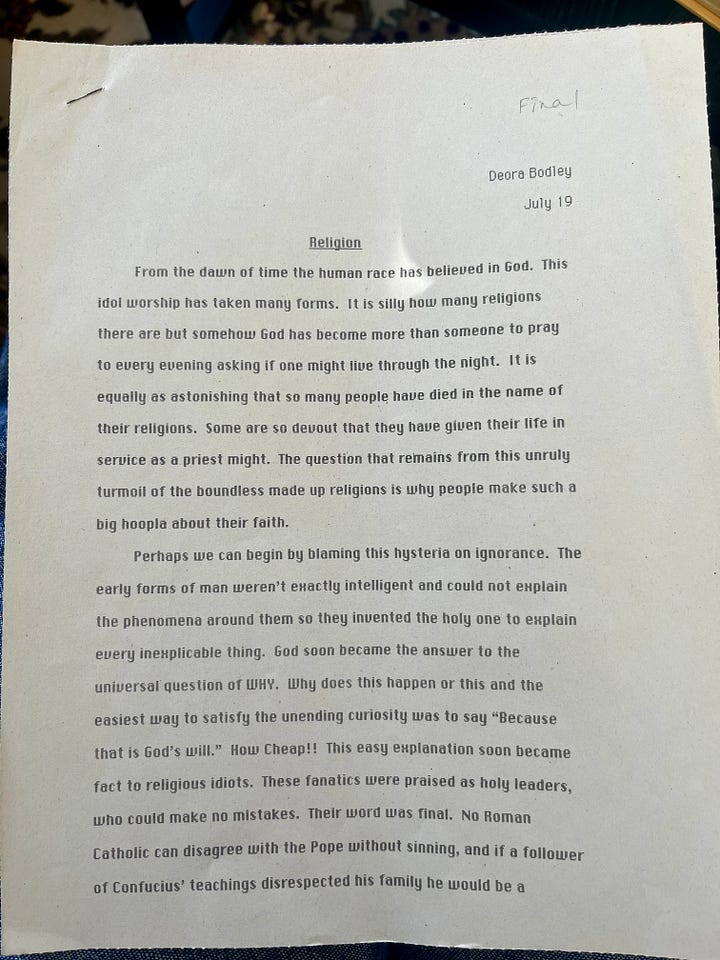

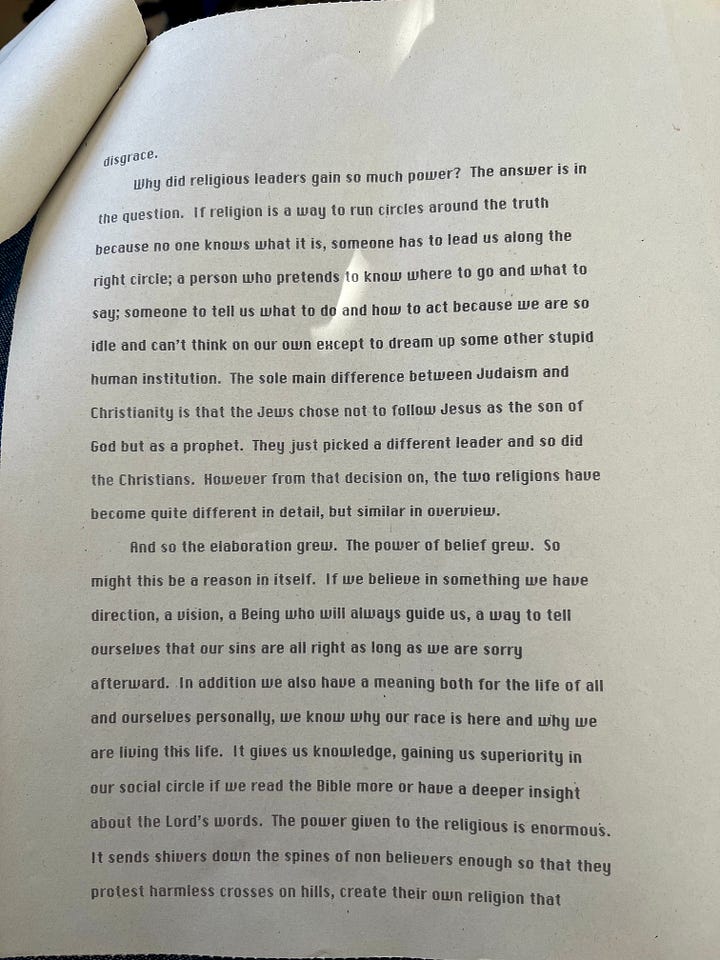

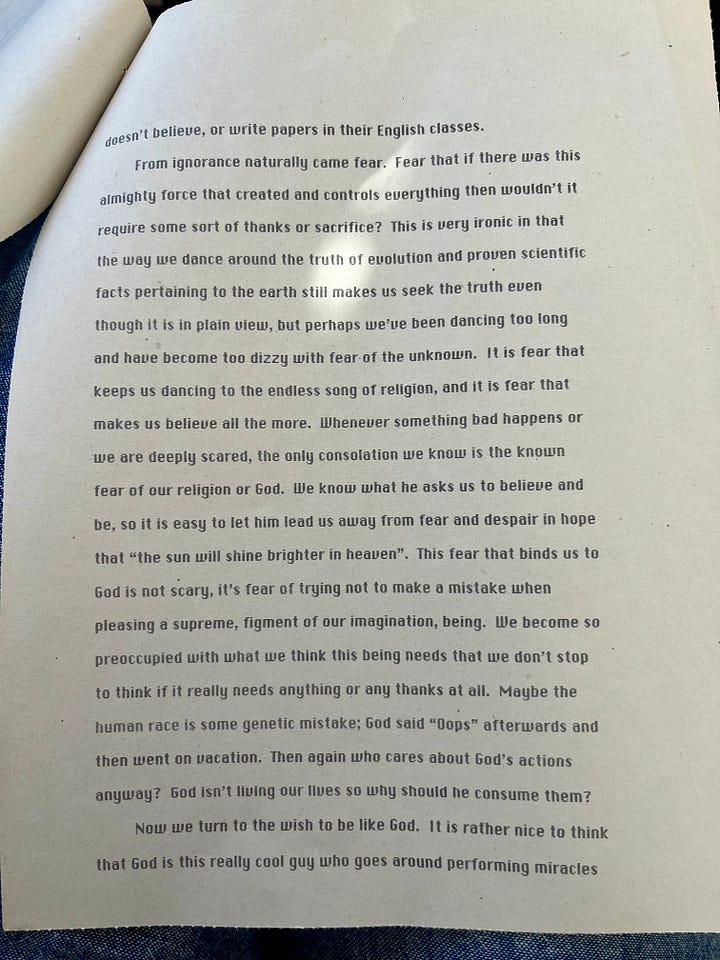

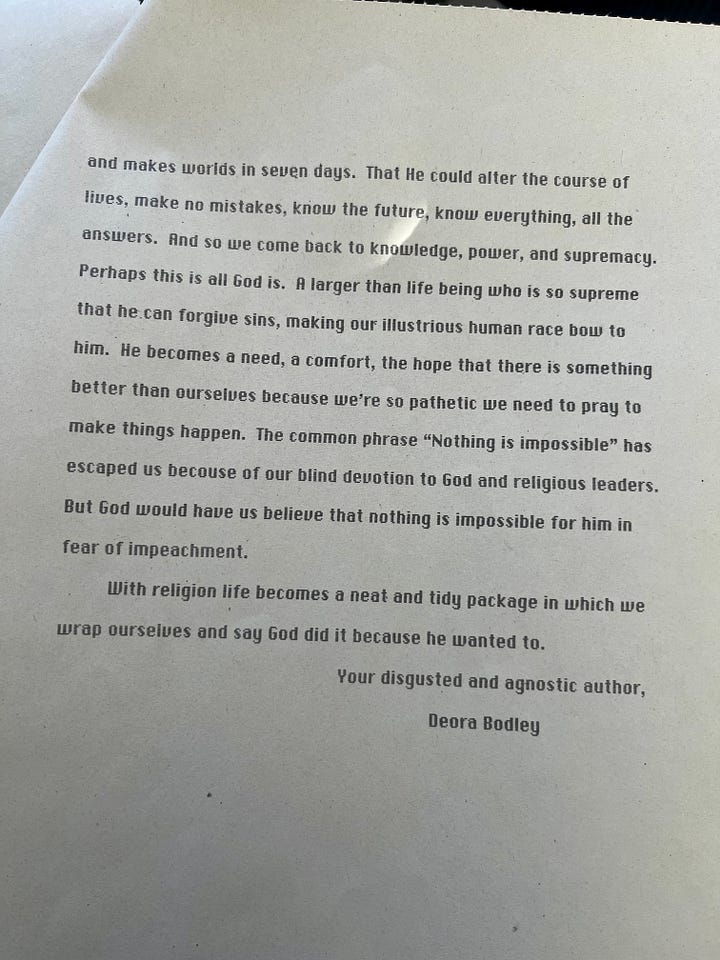

There were several selections that were so poignant, given what happened to her, they stopped me in my tracks. This essay on religion was one of them:

If you don’t have time or inclination to read it, it’s a scathing critique of religion, as an easy answer to unanswerable questions, as a means to control others and abuse power and cause harm, as a way of claiming superiority over others, as a repository of fear, as a way to make ourselves feel more powerful and invincible than we are.

“Perhaps we have been dancing too long and have become dizzy with fear of the unknown. It is fear that keeps us dancing to the endless song of religion, and fear that makes us believe all the more.”

A few years after writing this, Deora died because of this kind of religion. She was murdered by men dizzy from theirs, so drunk on having found certain answers to their questions, they could not abide any others. Other possibilities hang out there, mocking those certain in theirs, threatening to expose them as lies. To blow a puff of air towards a carefully constructed house of cards.

The 9/11 terrorists preferred to die than to confront their fear of the unknown. They figured if they were willing kill in the name of their faith, surely it had to be real. Surely they truly believed it. Surely it would save them.

As an evangelical, I was never tempted to do violence. But I would sometimes fantasize about martyrdom because it would be a final proof of my belief. Surely a martyr truly believes. Surely a martyr would be saved from hell, where I feared I would go for my weak faith. Surely dying for it would make it strong.

Deora is correct that, putting aside the validity of any particular faith, religion is inherently a fear response. It can become something much more; it can become a path of love and true faith, that lets go and lets be instead of claws and grasps at straws. But historically, on balance, that’s not what it’s been.

And that’s why Deora died.

This weekend I was at the Principles First conference, a pro-democracy event I’ve attended the last few years. This year I was a volunteer. It turned out to be more eventful than I anticipated. I’ll abbreviate things here, but you can read a more fulsome account on my Facebook page. There are also numerous media accounts out there.

The short version is the recently pardoned Thugs Formerly Known As Proud Boys1 showed up, fresh out of prison thanks to their patron Donald Trump, to menace participants of the conference. They were probably responsible for a bomb threat that was called in one of the days, although that has yet to be fully investigated. We were evacuated for over an hour while police searched the premises. Thank God no one was hurt.

I don’t think Chief Thug Enrique Tarrio is particularly religious, but many of the Thugs, as well as members of other far right terrorist groups, fancy themselves Christians. Of course, you can argue, as many have, that they are not really Christians. Certainly, they are not emblematic of the teachings of Jesus. But then, those seem to have little influence on the dominant strain of white American Christianity these days.

The Thugs, and other Christian Nationalists, want to take control of the government, forcibly if need be, in order to enforce their vision of society. They are the white American Christian version of the 9/11 terrorists.

Most white evangelicals are not Thugs or even less militant Christian Nationalists. But, honestly, the overlap is heavy. Most of these folks don’t have a violent bone in their bodies and are far more likely to serve dinner at a homeless shelter than to storm the Capitol and beat up cops. And yet, many, many are willing to believe the lies that undergirded that violence. And they support a movement that has fundamentally abandoned democracy. Because they have more fear than faith.

I didn’t grow up being taught to storm the Capitol if “our side” lost an election. But I did grow up being taught there was such a thing as “our side.” I grew up to think of other side as the devil. I grew up believing every Christian who didn’t believe *exactly* like us was going to hell. I grew up learning to minimize our tradition’s sins and magnify its greatness in comparison to others.’ I grew up with a distorted, dishonest history. I grew up believing that, as a woman, I was less than, or had to make myself less than. I grew up believing that we white Christians needed to correct the theology and ethics of Black ones. I grew up being told we had all the answers and all the goodness and all the love. And yet I didn’t feel much actual love, not for my true, flailing, struggling self. I grew up learning to hide. And I grew up in terror, every single day, that I was in danger of hell.

I grew up afraid, within a culture of fear. The white evangelical world view rests on a desperately overcompensating need to be right, and by virtue of their rightness, to win the culture wars and to convince, by law if needed, everyone else that they are right. I grew up on this. In fact, the only piece of Christian Nationalism that is new or shocking to me is the overt abandonment of democracy. That is new, because democracy isn’t working for the culture in which I grew up anymore.

In fact, instead of “winning,” many of its own children are leaving the faith. Despite hermetically sealing them in a home-schooled, evangelical bubble, still many of its children are leaving. The numbers of adherents are dropping, along with those of every other Christian or religious tradition in this modern, increasingly secular age.

And because white evangelicals’ faith, and their very identity, has been built on certainty and “winning,” they are now faced with an existential crisis. They are dizzy with fear. And as they stumble around trying to keep their balance, they are crashing into walls that have turned out to be the pillars of our democracy.

And they are grabbing on to people who seem stronger and more self-assured and more brutal to steady them. And those people are using them as human wrecking balls for their own ends.

I’ve got to believe if Deora were here, she would take out her high school essay and underline every word of it in red.

A religion of fear is why she died. And it is why America is dying now.

As you know, I myself am still a religious person. I honestly can’t tell you why. I go to church many times and bristle at some of the familiar evangelical songs that my liberal Methodist co-congregants have appropriated for the contemporary worship service. I really wish we could just add some drums to the old hymns and call it a day. But I think most other folks, who have far less spiritual baggage, enjoy these songs, and who am I to deny them their joy with my bitter heart.

Sometimes I sit in my chair and ponder whether any of it is true at all. Or worth continuing at all. I think of the destructive history of the church, of Crusades and Inquisitions and peddled penances and pro-slavery theology and white-hooded pastors and Baptist deacon lynching mobs and Baptist deacon predators and orchestrated cover-ups and historical revisions and missionary murderers and homophobic protestors and January 6 “Jesus Saves” banners and that stupid, f*cking cross around the neck of Trump’s sanctimoniously lying press secretary and all the myopia and arrogance and narcissism and callousness and fakery and ridiculousness and the utter denial of reality. And I think, there’s nothing redeemable here.

I read Jonathan Rauch’s new book Cross Purposes recently and was gob-smacked to see a gay, atheist, Jew argue that there is something redeemable. Or, maybe more practically, that we’re gonna have to find something to redeem in order to save American society, because the Christian church has been an American pillar and its toppling is a major danger. I can agree with that. Maybe he’s right that, in addition, there’s something beautiful buried under there. But it’s hard to accept that as someone steeped in it.

I wonder, like Deora, is religion itself worth it? In the collective (with significant numbers of exceptions), I far prefer the non-religious people I encounter, who seem more open, more curious, more accepting, more tolerant, more harmless, more fun, less angry, less burdened, less awful. As I myself have gotten less “religious” in the way I was raised, I have become a happier, healthier, more joyful, more peaceful, more creative person with richer relationships and a more meaningful life. Without even knowing what will happen to me when I die! Imagine!

Imagine.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion, looking at just the last decade, that we’d all be better off in a pluralist democracy without any religion at all, as people choose to abandon it.

And yet I keep going to church. Now more than ever, I feel drawn to it. I go to support Pastors Sara, Jeff, and Stephanie, whose hearts are weighed down for the immigrants and federal workers and LGBTQ people in our community. Who are looking for ways to provide comfort and help and support. Who desperately want Christians to follow Jesus’s actual teachings. Who try every day to seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly. I go because they are the kind of leaders we need.

I go to be with others who share my sadness and heartbreak and anxieties. I go to join my voice with theirs. I go to just sit amongst them in quiet. I go to work with them to reclaim and reshape what this ancient tradition is supposed to be, what it was before it became tangled up with power, hundreds of years ago. I go to get a bunch of hugs. And some ideas for what we can do, what we can say, how we should be.

I go because I am troubled by the anger and hatred in my own heart. I go to confront it and wrestle with it and make a little progress chipping away at it. To keep it from taking over. I go because I have been deeply wounded by Christians but still believe I might be healed by Christ. I go because somewhere, very deep inside, I must believe. I go in hopes that I do.

I go to hear the words of Jesus, who actually didn’t talk at all about what his evangelical followers are obsessed with, and who only hinted here and there about life beyond the here and now. Who never once tried to gain power or advocated for power or showed any interest in power. Who wanted to foment a revolution of love, in which power was turned on its head.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.

Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Imagine that Christ’s followers actually believed that. Imagine that a religion of exclusion and fear and control had not been built on top of it. Imagine how the world would be different.

I will keep dreaming. I don’t think I’m the only one.

A Black church won the rights to that name in a lawsuit against the group for vandalizing its property.

This could be my own spiritual biography. Thank you for voicing what so many of us feel.

I relate to so much of this...including this part: "I go to church many times and bristle at some of the familiar evangelical songs that my liberal Methodist [liberal Presbyterian, for me] co-congregants have appropriated for the contemporary worship service...But I think most other folks, who have far less spiritual baggage, enjoy these songs, and who am I to deny them their joy with my bitter heart." I feel so seen, lol.

I don't know that dominant white American evangelicalism is redeemable, but I think some form of Christianity is...which I want to think is what the majority of well-intentioned evangelicals tried to sign up for in the first place (maybe?)...