“What’s your major,” my history professor, Dr. Madden, asked me after class one day, in his quietly compelling Oklahoma drawl.

“Uh, Psychology?” I replied, with all the confidence of an American tourist sampling some kind of worm-based cuisine. I aspired to heal myself by healing others, a brilliant idea that works every time.

“Change it,” he said authoritatively. “You should major in history. You should get a doctorate.” It was like he had my entire life planned out.

I was glad someone did. Because other than a vague notion of specializing in eating disorders—and honestly, that was mainly for the dieting inspiration—I had zero idea what I was doing on adult planet earth.

I changed my major that day.

Less than a year before, I had graduated from high school after seven years at boarding school in rural Kenya, run by an American evangelical mission. It was and is probably the most insular micro-culture in the world, especially before the internet kicked in, as if created in a lab, and I was its otherworldly product, some kind of mongrel amalgam of cosmopolitan and sheltered, educated and naive, American but not quite. In that highly specific context, I knew how to take care of myself pretty well. I had my dysfunctions, but I also had friends, a sense of place, a community, and a home (not to mention a weak gag reflex that thankfully kept me from going full-on bulimic. It’s the small mercies in life that draw the fine line between irreparable and redeemable harm).

But then it was all over. The bubble burst, and I was sent flailing through space, not knowing where I’d land.

Where I landed was a small Southern Baptist college in West Texas my parents had attended and where they had long ago informed me I would attend. The average student there, from what I could tell, had rarely left the state of Texas or read a book other than the Bible, and the school’s location was a town only its native sons and daughters could find appealing. If my parents had wanted me to appreciate it, they should have never taken me to live in the Kenyan highlands, at the foot of Mt. Kenya, where the Kikuyu people have quite reasonably concluded God dwells. Other than the churches on every street corner, there was little evidence that a divine hand had ever grazed the face of this West Texas town.

But more honestly, the main problem with the school was I didn’t want to be there. And the main problem with the other students was that I didn’t want to know them. So I locked myself in a room and shoved my nose in a book and didn’t come up for air for fear I would have to breathe. Mostly I grieved without knowing it, because no one had died except for the girl I knew as myself.

Oh, and I got married at 19, but that’s another whole story. What can I say, I totally had my sh*t together.

Dr. Madden’s classes were a bright spot. His lectures were hardly that, more like stories told around a campfire. You could almost hear fiddle music in the background and feel hot chocolate singeing your tongue. He would half-saunter, half-limp into class, slightly hunched over from an arthritic back, enveloped in a lingering aura of the cigarettes he chain-smoked between classes.

He would prop himself up on a stool at the front, and ask, “Now where was I,” but only rhetorically, because he somehow remembered exactly where we had left off at the end of the last class. And then he would languidly unspool yarn after yarn, like some kind of mildly buzzed cat. He had no notes, no books, no visual aids, no schedule. His voice was quiet, even, and calm, his expression pleasant but unanimated.

By all standard measures of public speaking, his performance should have been auditory Ambien. But he held all but the most dull of us in the palm of his hand, rapt, eager to hear what would happen next, even when the stories were familiar.

He loved healthy sprinklings of colloquialisms and obliquely risqué details that usually went whizzing over my missionary-kid head. My boarding school had been an evangelical dream, a North Korea-like information environment that protected residents from almost all products of the non-Christian world. There was no TV, no radio, no phones. The movies screened for us on weekends were carefully selected, then edited so severely and poorly, it blew large holes in the plot. The Princess Bride could not be shown at all, because Westly being “mostly dead” and Miracle Max rehabilitating him from that state was heretical, yet too integral to the story to easily remove. There was no sex ed to speak of, other than dire warnings about the risks of fornication causing one’s life to spontaneously combust.

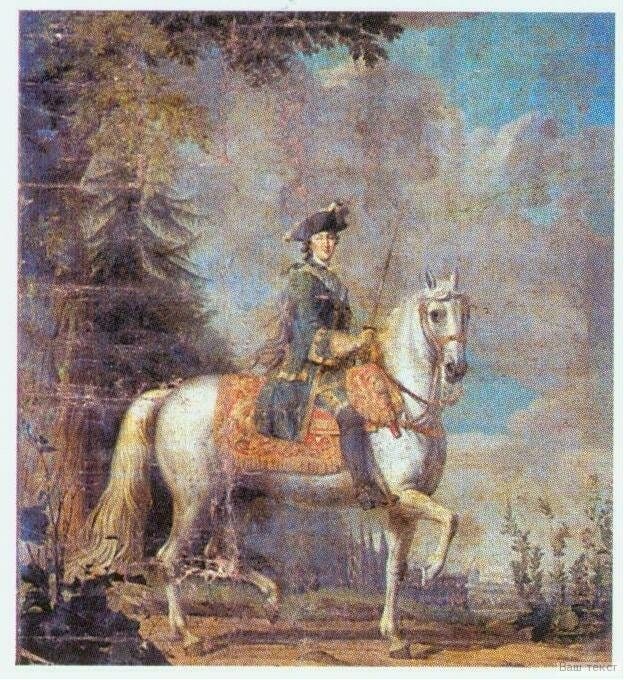

So when Dr. Madden would tell us, with a wink, that Catherine the Great “really liked animals. I mean she really, really liked them. Especially her horse,” I thought he meant she was a great equestrian. Or when he informed us that Alexander the Great was a “switch hitter,” I couldn’t come up with even a theoretical interpretation, knowing absolutely nothing about bisexuality nor baseball.

From what I remember and based on my subsequent education, the general facts he presented were true and the broad strokes of his lectures were accurate, although there were definitely sins of omission and emphasis. But you got glimpses of indisputably odd views here and there. A lecture on the Progressive Era might veer into a debate about the role of government in which he asked, I imagined rhetorically, why it was illegal not to wear a seatbelt. Eventually I would find out he never wore his seatbelt or followed any government mandate he could ignore without risking jail time.

He became obsessed with footage that made the rounds in the mid-90s of a supposed autopsy performed by government scientists on an alien recovered from a UFO crash in Roswell, New Mexico in 1947. He asked, I thought satirically, if the government hid this from us, what else was it hiding? Maybe FDR really did know about Pearl Harbor ahead of time.

And then there was his take on the holocaust. He didn’t dispute that the Nazis were pure evil. But how did we really know how many Jews were killed? And how were those deaths different from the more mundane horrors of war? Was Hitler worse than Stalin, with whom we allied? He never outright said the holocaust didn’t happen, he was “just asking questions” and provoking us to “think for ourselves.”

Also, how did we know exactly that Hitler killed himself? Did we have evidence that he didn’t escape on a secret Nazi spaceship that rode on the Van Allen belts? I thought he was joking.

To his credit, he let me organize a trip for our history club to the holocaust museum in Dallas, which could not have been a great time for a holocaust denier. But he went and even drove us there himself, seatbelt-free, of course (we all wore ours). There, we met with a holocaust survivor, to whom he listened respectfully. He thanked her politely at the end without saying another word.

I was mostly blind to Dr. Madden’s eccentricities and instead wholeheartedly believed in his goodness. Because he believed in me, and he was good to me. As I mourned my past, he kept me focused on the future, the things I could accomplish, the heights I could reach, the person I could be. As I neared graduation, he helped me apply for graduate school. As it turns out, he didn’t have a great grasp on what made a good graduate school application, but he tried. I ended up at his alma mater, not the best school for my field, but it turned out to be the best place for me. It was where I found the ideas and the community and the work that brought me back to life. Dr. Madden set me on the yellow brick road I needed to follow to find my way home.

My third week of grad school, I called him crying. I was drowning in assigned reading, which averaged hundreds of pages a day. I was spending every waking minute reading and not getting much sleep either.

“Wait a second,” he said. “Are you actually reading everything? Like every word?”

“Yes? Isn't that what I’m supposed to do?” I sniffled.

“No, no, no. You can’t read all that. No one can,” he replied. “You need to learn to skim.” He then spent an hour or so giving me speed reading tips that freed up hours of my days and taught me to isolate and evaluate main arguments. After that, I was good to go.

Several years later, he gave me a job. I wasn’t yet finished with my dissertation, but there was an opening in the history department, a tenure track position no less, and he wanted me to have it. Although I wasn’t terribly thrilled to return to West Texas, I knew this was my best shot at an academic career. And so, Dr. Madden became my colleague.

And that’s when I realized he wasn’t merely eccentric, he was several sheets to the wind, a full-blown conspiracy theorist of the most noxious kind.

I sat with him in staff meetings, where he didn’t just ask provocative questions, he openly spouted bat sh*t, offensive things, including that the holocaust was overblown, that the Jews had not suffered more than the general population, and that claims of genocide were made in service to larger agendas. Like many anti-semites, he didn’t dislike Jews per se, his issue was with The Jews, the powers that be, the elites. Similarly, I don’t think he minded the government, but he imagined some phantom, overlord Government that pulled invisible strings in ways that used and abused ordinary folk like him. At heart, he was a part-Native American boy from rural Oklahoma who dropped out of high school only to rediscover education in his 30s and go from GED to Ph.D. in eight years. He had pulled himself up by his bootstraps (which he actually wore every day) and despite the best efforts of society’s elites who didn’t want to see folks like him succeed.

Also, he was serious about the Van Allen belts.

Oh, and his best friend was the French and German professor, who I had also had as a professor, an amusing but creepy German American man who had legit been in the Hitler Youth as a boy, although not by choice (he claimed). But Dr. Schubert also turned out to be far more disturbing a personality once I was no longer a student, lecherous and racist. Although, as he would say in his defense, his fifth wife was Thai.

If Dr. Madden were still alive, I have no doubt he’d be a Qanon believer, a vaccine skeptic, a Trump supporter, perhaps even a Christian Nationalist, although he was never terribly religious (there were many professors at that evangelical school who had obviously signed their statements of faith with fingers crossed behind their backs).1 He’d probably be all the things that vex me most and keep me up at night worrying for the state of this nation. (If he were still alive, Dr. Schubert would probably be in jail).

And that’s the unsolvable riddle that is a human being. That the well-educated could be so misguided. That a historian could fail to see history. And that a person who had lost his way on some level could help someone else find theirs. That a heart could be dark and gold.

What we believe does matter, particularly if it’s pernicious. I think we’ve seen that clearly these past several years. I would never excuse toxic, dishonest, bigoted ideas or the deadly, horrific damage they cause. And many of their proponents are pure evil, with nothing good in their hearts to salvage.

But belief isn’t the entirety of who we are as individuals, or it shouldn’t be. And as either proponents or critics of systems of belief, we should strive to be multidimensional people and connect with other people apart from our beliefs. That’s where redemption might be found. That’s where authentic relationship can thrive.

I grew up in a system of belief that, while increasingly overcome by its inherent flaws and contradictions, was and is lovely in many ways. I still believe the true message of Christ is beautiful, though history and our current day is full of violent distortions that create intersections between Christianity and bigotry and abuse, antisemitism itself being one example. But I’ve also seen people resurrected and restored by the Gospel, and my own family members have been inspired by it to serve and sacrifice for others. On balance, what I grew up with tips more toward the positive. I want to make clear that I am not at all equating Dr. Madden’s beliefs with that of my upbringing.

But I’ve also known how even a generally positive belief system can be so all-consuming, it becomes a barrier to what I consider the ultimate, tangible truth of human connection. It was for me as a true believer. All of my relationships and interactions ran through a filter. Belief, no matter how untestable and baseless, trumped the flesh and blood people standing in front of me every time.

On the other side of that belief system, I can see the flip side, the walls that can go up around the rejection and criticism of others’ belief, no matter how justified that condemnation may be. The gravitational pull of going all the way around the bend. The danger of seeing people’s beliefs as the only thing about them. The risk of turning people into cartoons (and again, it doesn’t help when that’s how some believers present themselves, but that’s still no excuse).

Dr. Madden continues to teach me all these years later, long after he’s been gone. As I confront beliefs I find to be dangerous, and as I make my way through a time in which history is being made and the future and the past join together to urge us all to Speak up, Speak out, Do something!—I remember that a holocaust denier saved my life. He couldn't see many truths, but he saw the truth of who I was and what I needed.

And I am reminded that people are complicated, and the people in my life who cause my head to explode with their rigid, stubborn, and often toxic beliefs exist in better, truer form somewhere beneath them.

It’s up to all of us to do some excavation.

It’s also clear that the spiritual standards for faculty were generally quite low there for awhile. The fundamentalists who took over the Southern Baptist Convention would probably point to Drs. Madden and Schubert and any number of others as evidence of liberals being in charge. Of course, they have also enabled their fair share of racists, abusers, and crazy people.

I was raised in a very Catholic home, where we prayed the Rosary together and went to Mass every Sunday. Nonetheless after being introduced to physics I dropped any belief in a God. Still I continue to think of Jesus sayings and hope to live by them. Married almost 50 years - my son was not baptized nor churched in any way. Still he seems to have absorbed my moral beliefs and even my prudery.

Re religion, I still admire those dedicated to good works (such as the Catholic Worker types). Jesus' teachings are stilll worthy even today.

Thanks for sharing your background, these experiences, and the wisdom lessons you derived from them. I think that so many of the stressors in our current social environment could be mitigated substantially if more of our fellow "travelers" on this journey would accept, as you have related, that life is complex in many ways, that who we are today has been formed and influenced by a multitude of factors (only some of which we have invited, controlled, or even recognized at the time), and that everyone else is also multi-dimensional in that respect. By employing patience and generosity of spirit in our interaction with others, perhaps we can help rebuild the social capital that has been squandered over the past decades by reductionist fundamentalist tribal mindsets and identity-based exclusive behaviors of all kinds. This is often frustrating in practice, but we need to realize that such efforts are an ongoing requirement (like protecting democracy and building an equitable society), not a "one-and-done" task. Seeing each individual as a whole person to the extent possible is a necessary, but not sufficient condition, for progress with our families, friendships, colleagues, and communities. May more people evaluate their own life experiences in the wonderful, insightful way you have done.