(This is one of a series of posts about my childhood as a missionary kid in Kenya. You can find other fun tales under the tag “Memoir.” They are drawn from a manuscript rejected by various agents and publishers.)

I almost started a political riot by doing the bunny ears.

For those under 40, the bunny ears were an ancient ancestor of the photo bomb, and you'll still see old and/or really socially awkward people doing it on occasion. You make a "V" with your index and middle finger, then surreptitiously put your hand behind someone else's head right before a photo is taken, making them look like they have become a rabbit. It's so embarrassing for them. No one wants the implication of being a small furry creature with large ears. That's why it's a great practical joke. See?

It was 1992, and my senior class at Rift Valley Academy (RVA), the American missionary boarding school in Kenya I attended for seven years, had just returned from Senior Safari, the long-awaited, hard-won trip to the Kenya coast that occurs just before graduation every year. We eased back into Nairobi station and poured out of the train, cracking a few last jokes and taking a few last pictures. We embraced in large groups, smiling the toothy, smooth grins of adolescence. And then, I did the bunny ears.

The train station instantly exploded into a cacophonous flurry, like an opened-up wasps' nest. Men ran toward me, some with one finger raised, some with two (a.k.a bunny ears), yelling at each other, their eyes animated and fierce. The one-fingered crowd shouted, "KANU! KANU! KANU!," and those bearing two replied, "FORD! FORD! FORD!" Horrified at the mess I had made, I desperately cried, "No! Bunny ears! BUNNY EARS!" Our teachers quickly ushered us out of the station and into our waiting bus, leaving Real Kenya with its political turmoil behind us. Growing up a privileged, white American there, this was always our prerogative. I spent my childhood peering out at this country I loved but to which I did not really belong through the shimmering walls of a bubble.

In 1992, Kenya's usual, government-controlled tranquility was unraveling. Two years before, President Daniel arap Moi and the country's founding KANU party had relented to pressure from democracy activists and western powers--who found his corruption and repression less tolerable as the Cold War ended--and allowed multiparty democracy for the first time since the early days of the Republic, when Kenya's first president, Jomo Kenyatta, had consolidated his authority and quashed any dissent.

As political scientists will tell you, democracies are much more peaceful and stable than autocracies, but democratizing countries are incredibly volatile, like a shaken-up bottle of champagne with its cork inching out. In the 1990's, Kenya's politics descended into previously contained tribal animosity, as Moi found stoking it a convenient new weapon for the multiparty age. The houses and farms of opposing ethnic groups were burned, opposition activists clashed with police, and thousands of ordinary Kenyans died.

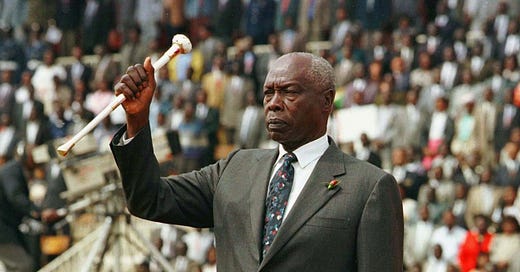

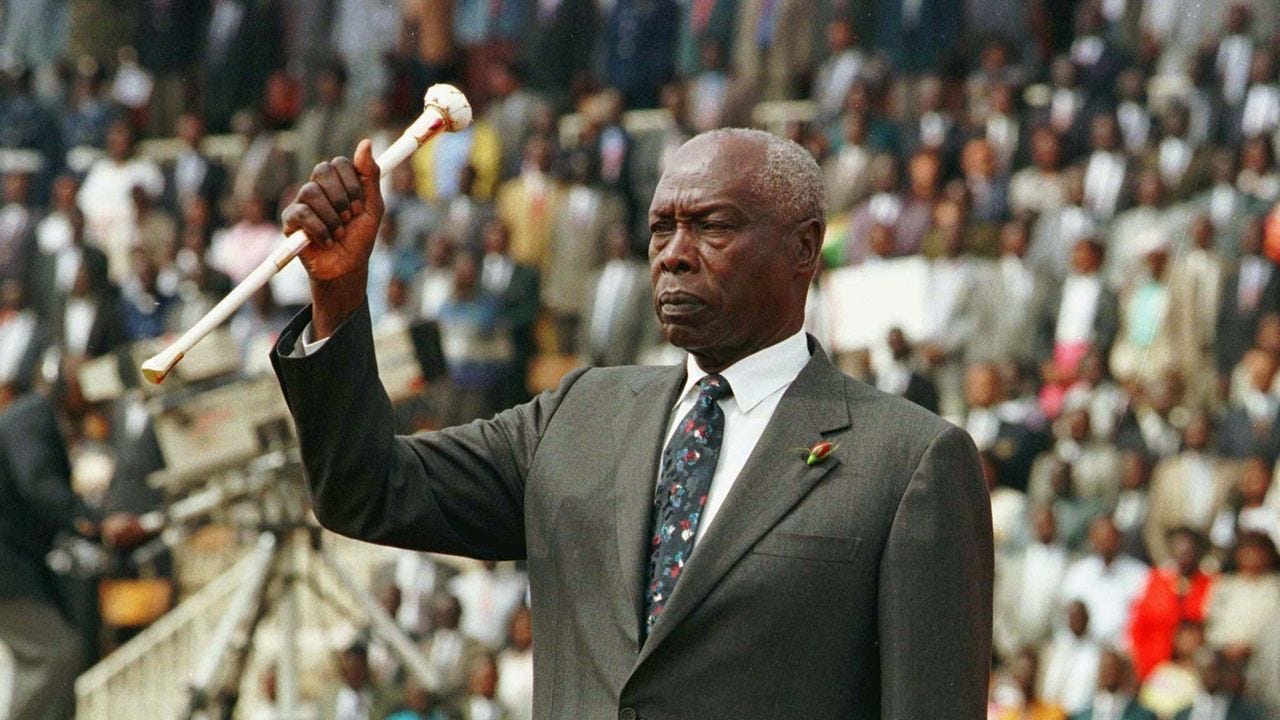

By then, I felt I kind of knew President Moi, he was such a ubiquitous presence in my childhood. His picture hung in every room in every public building and in many people's homes. The first of several times I saw him in the flesh was while I attended a Kenyan primary school in Nyeri, the Aberdare Mountain town where my family lived. Our teachers ushered us out to the main roadway and ordered us to shout his nickname "Nyayo!" as his motorcade went by. His car slowed upon its approach, and he stood up through the sunroof, waving his trademark decorative rungu at us to receive our forced adulation. He also made a few visits to the greater RVA community while I was there, as he was a highly devout (in his own mind) member of the African Inland Church, an affiliate of the mission that ran RVA that was based in the nearby town. He had grown up working in the home of American missionaries from the African Inland Mission.

He made an "official" visit to RVA itself my second year there, in 1987. School was cancelled, and we all turned out in our Sunday best. One of my classmate's adorable six-year-old sister was chosen to present the president with flowers upon his arrival. The choir sang for him, he was given a tour, he chatted with the staff, ate lunch, then headed out. We lined the road and cheered him as he left. Then, right in front of me, he stopped his car, rolled down his window, and motioned for me to approach. I hesitated for a moment, then did as he asked. He handed me a box of candy and gum to distribute to the children. I looked him in the eye and offered my thanks. He gave a slight smile, revealing many missing teeth, nodded, and went on his way. I had no reason to doubt his goodness. At that time, most of his crimes were safely tucked away in the pockets of the cloaks he wore—Christian, Cold Warrior, geopolitical friend to America, Kenya's genteel elder statesmen, who offered candy to children. No one spoke ill of him then, and I believed that was because there was nothing to say. But as I neared my high school graduation, the cloaks were threadbare and the pockets were emptied, their ugly contents--grand corruption, abuse of power, violence, torture--strewn on the ground.

My senior year, my family moved to Kericho, in the multiethnic western part of the country, taking with us one of my parents' former students to work in our house. James was Kikuyu, the tribe that was now leading the resistance to Moi's rule and that was in the minority in Kericho. James was mostly welcomed at first. He started side businesses and a street kid ministry and became a popular member of his church. On an average day, without political interference, Kenyans of all tribes interacted, did business, intermarried, became friends, and lived in peace. But as the election grew near, James became more and more frightened, and one day, my parents returned home from a trip to find him sleeping on the roof of our house. It was the only place he felt safe from gangs of Kalenjin men who had begun roaming the town, menacing the Kikuyu.

At school, too, we got glimpses of the trouble brewing outside our bubble, isolated on our perch above the Rift Valley and above the fray. Our junior year, in 1990, a new girl arrived at school. No one overtly made the connection between her enrollment and the latest headlines regarding the suspicious death of Moi's increasingly insubordinate Foreign Minister, Robert Ouko. He supposedly shot himself, according to the authorities, yet he somehow managed to burn his own body. I never heard my classmate say a word about her father, and few of our Kenyan schoolmates commented on the seemingly distant political turmoil that was actually terribly close for them. I did get into an argument with one of my Kenyan classmates over the United States' (decades-belated) pressure on Moi to hold the election and bring democracy to the country. I couldn't fathom how she didn't see America's noble intentions, that democracy was every person's birthright, and that Moi had to be called out. "You don't understand," she said, "Democracy is a good thing, but the cost is so very high. America needs to leave us alone and let us figure it out."

She had a point. If things went south, we Americans would all get out. We claimed to love this land. But the hard fact was very few of us would ever tie our fates together in a gordian knot. We kept our livelihoods, futures, blood and treasure elsewhere while we drank in Kenya's beauty and bathed in her warmth, like an exploitative lover who will never leave his wife. We believed we were there to help, we believed people needed us, we believed we made a difference in their lives. But we would not stick it out. That was true whether there was war or peace. Our time had an end, our departures were certain. We were not fully committed to this place.

We rehearsed for that inevitability. At the urging of the American Embassy, RVA began running contingency drills. In the event it became necessary, we were told, US Marines would arrive to evacuate us. It wasn't clear what would happen to the non-Americans among us, who comprised a sizable minority of the student body and staff. But we were all told to keep a small bag packed with some changes of clothes, our passports, and anything else we would want to take with us if we had to flee. We practiced going to assigned gathering points with our bags given the sounding of a particular alarm. The girls gushed about how exciting it would be to be evacuated by some hot Marines, pretending a hormonal rush could offset the fear and loss (and that a Marine might find the wherewithal to fall in love with a high school girl while evacuating an entire school).

Thirty years later, Kenya is in a much better place. In 2002, Moi voluntarily stepped down-- again under pressure from the US--the ruling party lost, and Kenya had its first peaceful transfer of power. President Kibaki ended political detentions and opened up the torture chambers to the media. But the country's institutions remained underdeveloped, and Kibaki would fall prey to the corrupting influence of power. In 2007, he won reelection through manipulation of the vote tally, unleashing an explosion of violence between protesters and police and between rival ethnic groups. Over 1,000 people died. The international community, including the US, once again intervened, pushing Kibaki and his rival join hands in support of drafting a new constitution that has provided a framework for more stable democracy. In 2013 and again in 2022, Kenya enjoyed two more peaceful transfers of power. Kenya still has a lot of problems—corruption, crime, poverty, occasional political turmoil. Right now, the loser of the 2022 election is leading protests denying the results (hmm, sounds familiar). Democracy is not an event, it’s a process, one that will continue to unfold for Kenya. But the trajectory of forward.

As I've watched my beloved Kenya move forward, I've watched my other cherished country, the United States, regress. As authoritarianism recedes in the one, it menaces the other. As ethnically-based tribalism begins to subside in Kenya, political-cultural tribalism rages in the United States. In both cases, tribalism has caused otherwise decent people to fall under the influence of power-hungry leaders, who stoke fears of the other side screwing them over and snuffing them out. In both cases, there is a lack of trust in neutral institutions and systems to enforce rules and mediate disputes.

In Kenya, that mistrust has been well founded, as elections have too often been unfair and the executive has been unchecked. It's been so gratifying to see credible institutions--like an independent Supreme Court that has repeatedly ruled against a sitting president, in 2017 even nullifying a presidential election--slowly developing and winning Kenyans' trust. The result is more peace, more democracy, more stability, and economic growth (although sputtering at the moment).

And it's been incredibly distressing to see America heading in the opposite direction, as too many Americans, without evidence, abandon all faith in our institutions and break long established rules in a desperate attempt to triumph in a cultural contest they feel they can't win democratically. I want to shout from the rooftops, "STOP! NO! I know how this story ends! You don't want to go there!" It's frankly ENRAGING to see my fellow citizens so casually throw to the side what people around the world continue to risk and sacrifice so much to grasp. This is not theoretical to me. I've seen it with my own eyes. And now I can hardly believe my eyes.

As a dumb kid in Kenya, I didn't fully register the importance of what was going on around me. I didn't really understand I was watching a precious democracy trying to be born. I mainly feared losing my home, having to flee. I lost it anyway, not from political turmoil, but because it was never really mine. I had to grow up and become a Real American. As personally painful as that was, excruciating really, I knew, even then, what a gift my citizenship was. I knew it was a ticket to ride many people around me would have loved to possess. And I knew that ticket was punched by stable, thriving democracy, the guarantor of the whole thing, what gave us the peace and prosperity and opportunity that Kenya sadly lacked.

And America's best export. The other thing I picked up on as a child was my "passport country"'s influence. Not always positive--certainly, during the Cold War, the US excused and enabled the Mois of the world--and sometimes complicated and fraught, as my friend pointed out, but I understood even back then that America was power, and power could ship in thousands of pounds of food aid, like I witnessed during the 1984 drought. And it could bring a dictator to his knees. And it could eventually help him to the exit. And support ordinary people in building something better in his wake. If American democracy goes by the wayside, or even if America retreats to its shores, it's not just Americans who lose.

When I've gone back to Kenya, and elsewhere in Africa, over the last several years, my conversations with Africans have had a different tenor than before, when we would bemoan the state of their countries, the stubborn corruption, the destructive tribalism, the persistent poverty. And all of those things remain problems for Kenya, despite the progress over the last 30 years. But now we also talk about America, and what is visible even from afar, that this behemoth is in danger of falling over. We talk about gun violence and racism and corruption and diplomatic disengagement and, in the last few years, January 6. They know as well as I do that American elections aren't supposed to be violent. They are shaken by it all. They are now consoling me.

If a giant crashes to the ground, the impact is felt far and wide. And if American democracy can't make it, with its 250 years of experience and entrenched institutions, what hope does Kenyan democracy have?

Americans, please, cherish what you have. The whole world is counting on it.