(This is one of a series of posts about my childhood as a missionary kid in Kenya. You can find other fun tales under the tag “Memoir.” They are drawn from a manuscript rejected by various agents and publishers.)

For most of my childhood, our family lived in Nyeri, Kenya a breathtaking place between the Aberdare Mountains and majestic Mt. Kenya, a 17,000-foot, snow-capped anomaly almost exactly on the equator. After a a year and a half of migrating from one weigh-station to the next while my parents were in various kinds of missionary training, under a constant barrage of new people, schools, and routines and with most of our belongings in storage, I was relieved to be settling down in what felt like a real home. We were reunited with our cherished things, as we unpacked toys, furniture, mementos, and photographs we hadn't seen in a year.

My parents had shipped virtually everything they owned to Kenya, as the move counted as a final one funded by the military after my dad's retirement. This meant we had an unusual amount of stuff and a higher standard of living, at least in appearance, than most other missionaries, who came with the bare necessities and made do with what they could find in country. Our house had fine china and polished silver, necessities for entertaining on the military officer scene but not exactly practical in rural Kenya. We had carpets and bookshelves full of books and a Hummel figurine collection and Asian art from my dad's deployment to Korea. There were gorgeous wood-carved German clocks and a piano. There were extremely poorly-considered cream colored sofas that had no chance of staying that way. We were by no means rich, but by missionary standards, and definitely by African standards, we certainly looked it. Either rich or completely insane.

We had a massive, wooded yard with a grassy hill that we slid down on boxes after the lawn had been mowed. You could almost see Mt. Kenya from our yard, but for a neighbor's tree that my mother threatened to cut down in the night, not to mention the mountain's modest personality and magical ability to completely disappear behind clouds. There was a fragrant rose garden and a giant avocado tree that yielded enough fruit to bathe in guacamole every night (we didn't ever do that). There was this really awesome gutter that channeled all the (hopefully) non-sewage water waste from the house into the vegetable garden. My sister, Laura, and I made little boats for our dolls and had them sail away down the channel on exotic vegetable-themed vacations when my mother washed clothes. The rest of the time, the dolls lived in mud-clot houses we made for them in the flower beds or huge civilizations we erected for them in our rooms out of cardboard and various other trash.

The house was a bit less impressive than the yard, probably not my mother's dream house, but it was fine. It had a functional kitchen, linoleum floors, decent plumbing and electricity, sometimes, plastered walls and, like most houses in Kenya, a tin roof that sounded like Enya had landed every time it rained. Rain on a tin roof is still one of my favorite sounds in all the world. The house had a lovely veranda overlooking the rose garden on which I would lay for hours as a teenager, slathered in baby oil, hoping to get a tan despite all indications of it being a genetic impossibility. It had a laundry room with a sort-of washer hook-up, in that there was a hook-up, but not the water pressure needed to fill the machine that way. So my mother filled it manually with a hose instead. This worked fine 90 percent of the time, when she didn't forget she was filling the washer and accidentally flooded several rooms. That only happened a few dozen times though.

My sister and I had our own rooms in our new home, technically, although they were connected by a doorway, and you had to go through her room to get to mine. The house had once ended halfway through my sister's room, and I guess someone decided there should be another bedroom and the easiest way to achieve that would be to simply build it right next to the other one. When we moved in, I wanted Laura's room so badly, because it had a built-in vanity with mirrors on three sides and uber-flattering florescent lights at the top. But she got first dibs and wanted the vanity, too. It turned out to be a horrible choice on her part, because I still found plenty of time to gaze at myself in the three-way mirror while she read, for hours at a time, sitting on the toilet. In addition, I got to annoy her to no end barging through her room to get to and from mine. Laura usually makes good decisions, but that was certainly not one of them. It reminded me of another epically bad one, her choice of an ugly, plastic-and-wire, 70's-looking knick-knack when our great-grandmother let us pick out something of hers to have. I'm sure that hideous thing is in a landfill somewhere, while I still have my beautiful antique doll wearing hand-crocheted clothes.

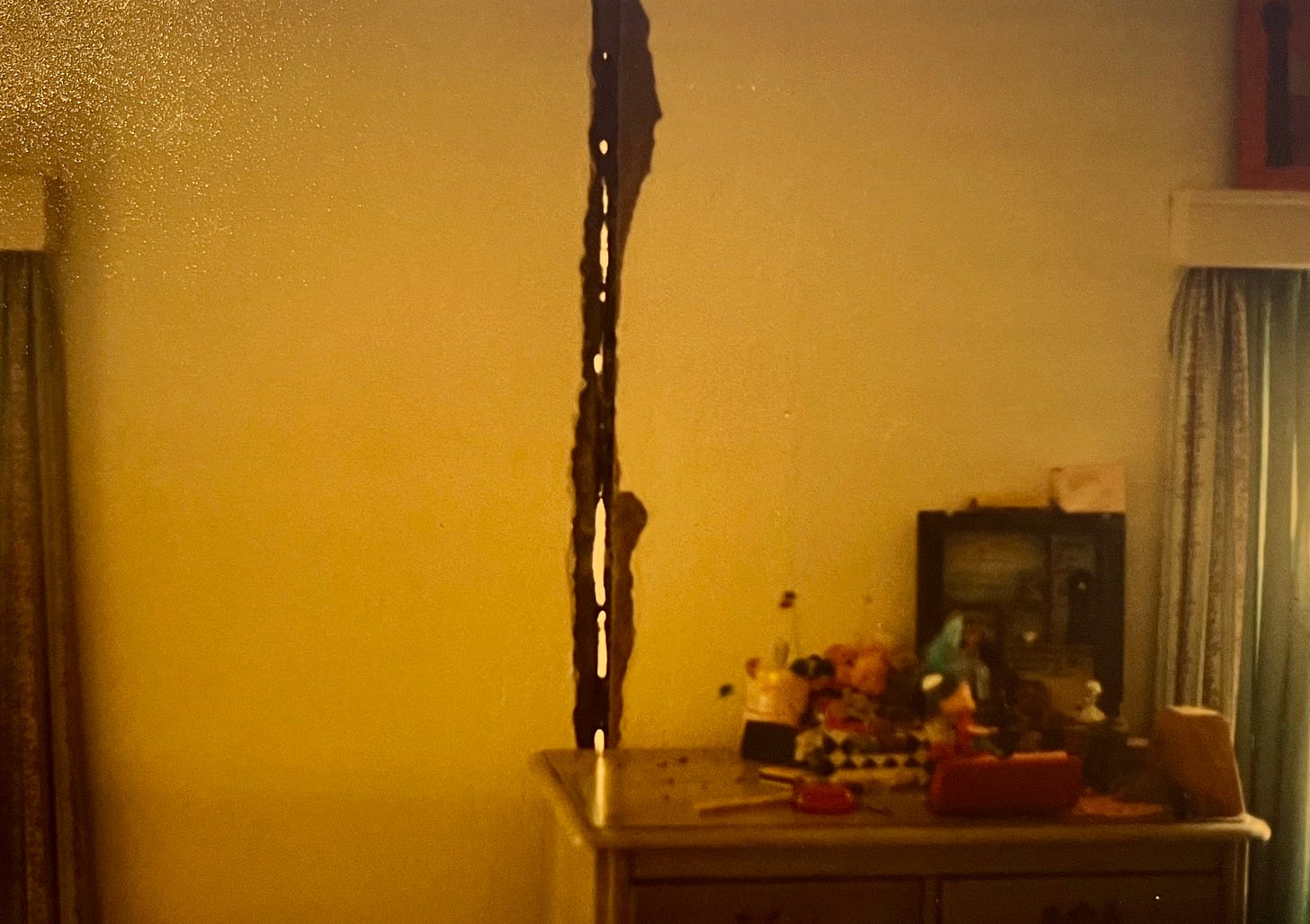

But the worst thing about Laura's room was The Crack. Whatever brilliant person decided to add on a bedroom next to a bedroom also decided there was no need to connect the old and new portions of the house structurally. They just dug a hole, knocked out a wall and laid some bricks down beside the old ones. As a result, there was a huge crack—and calling it a crack is an insult to its qualifications—that ran floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall. It was almost like maybe a drainage ditch or ventilation system or mini-window. You could see light and feel air through that crack. You could lose items of significant size in that crack. I'm surprised my sister, being as thin as she was, didn't just fall through it into the earth's core. And of course, various critters loved crawling through it, thankfully just bugs and lizards, nothing too frightening like mice or Satan.

When we first moved in, my parents were concerned about The Crack, and being naive Americans, they thought they could do something about it. They measured it and monitored any changes in its girth. They had someone who claimed to be an engineer of some kind—which in 1980's Kenya meant he owned a tape measure and could operate a calculator—come and look at it. This guy tried to patch it with some cement and inserted these plastic things which were supposed to alert you if the house was about to completely fall apart. I'm not sure what you were meant to do in that case, perhaps build a new mud-clot home in the garden, but you would be alerted. Probably even alarmed. Now Laura not only had a massive crack in her room, she had an ugly cement attempt to fix it and these weird plastic things in her walls. But at least she could still admire her reflection in her vanity mirror.

The Crack did indeed get wider, but I'm not sure if or how the plastic things alerted anyone. Thankfully, the house never fell apart. Nor did it get fixed. Pretty soon, even a fully grown Laura could have exited the house through The Crack (the rest of us are too fat). We all just lived with The Crack.

It became one of a huge number of things in Africa that my parents found they could not control, master, or even understand to any significant degree. I, being a child, had the luxury of not being responsible for any of it. I could devote all my energy to climbing the avocado tree, marveling at the brightness of the bougainvillea hanging overhead, and soaking up the warm equatorial sun.

A fun read! Thank you!

I sense a metaphor!